This article is adapted from a one- day workshop offered by Sylvia Boorstein at the Bane Center for Buddhist Studies on April 5, 1997. Since that time, Sylvia has also taught a ten-week course on Paramis at the Spirit Rock Meditation Center in California.

W e begin this day of practice in the traditional way of honoring the Buddha and all those others who have awakened to the possibility of living a fully wise and compassionate life. We take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

e begin this day of practice in the traditional way of honoring the Buddha and all those others who have awakened to the possibility of living a fully wise and compassionate life. We take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.

When I reflect on what it means to take refuge in the Buddha, I often think that the Buddha was a human being, just like us, and we share with him and with all awakened beings that capacity to see clearly, to be fully awake, responding always with kindness and compassion. It’s very thrilling for me to think about that capacity and to use awakened beings a role models.

When I think about taking refuge in the Dharma, I think about what a relief it is to have had so many people practice before me. I don’t have to reinvent the wheel. The fact that the path of practice has worked for so many others gives me confidence that it can work for me as well.

In reflecting on taking refuge in the Sangha, I think about how fortunate I am, how fortunate we all are, to have friends and family and a community of people who are eager to support us in our practice. I am grateful to all my companions who share with me the sense of the inevitable challenge of being alive as well as seeing the possibility for living life with grace and appreciation.

Let’s sit quietly for a while together and use our reflection of gratitude for the possibility of practice to inspire our zeal to study together today. You can further inspire your dedication to practice by reflecting on your motivation for practice. Perhaps you’ll feel inspired, as I do, by the verse from the Dhammapada which carries the triple imperative to turn away from all evil-doing, to do what is good, and to purify your heart. I am always inspired and motivated in my practice by my faith that this possibility exists.

sabbapāpassa akaraṇaṃ

kusalassa upasampadā

sacittapariyodapanaṃ

etaṃ buddhāna sāsanaṃNot to do any wrong,

To cultivate doing good,

To purify one’s heart—

This is the Buddhas’ teaching.Dhammapada 183

This is a day about cultivating the pāramīs, the fully cultivated mind and heart qualities of a bodhisattva, of a Buddha, of a fully awakened being. One of the roots of the word parami conveys the sense of “supreme quality.” Pāramītā means “going toward” something, going toward perfection.

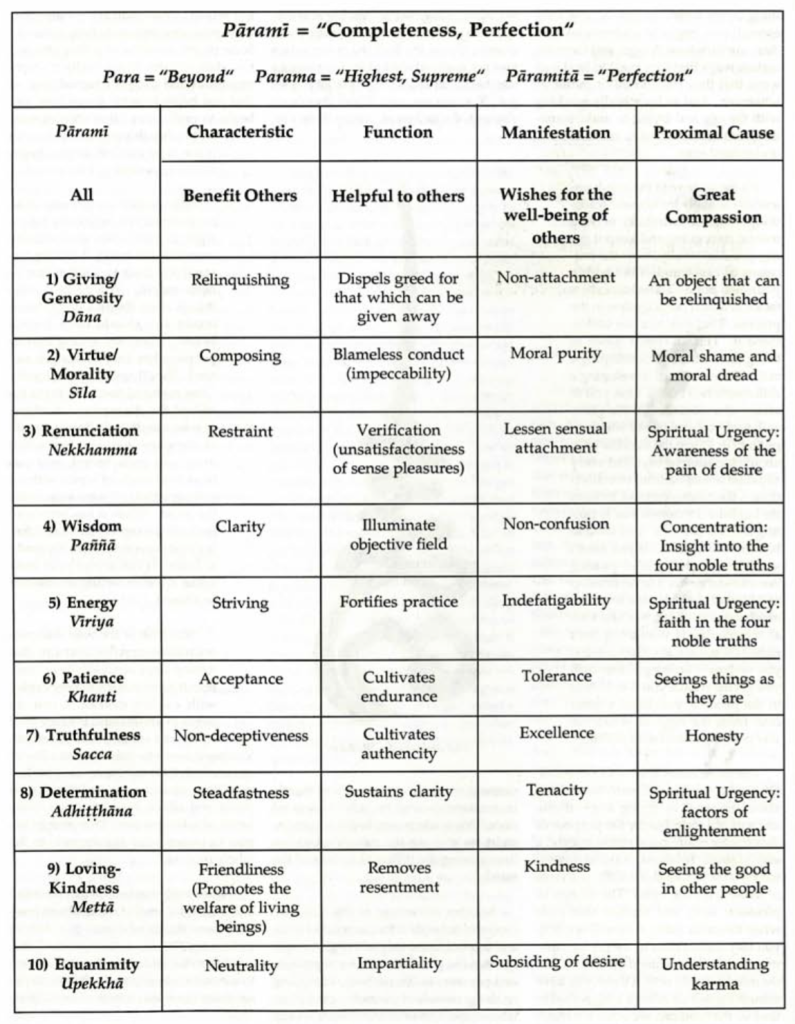

In traditional texts, the ten paramis are presented in a particular order, beginning with generosity and ending with equanimity. In preparing for our workshop today, I constructed this chart, listing the ten paramis, their characteristics, functions, manifestations, and proximal causes, using the text in A Treatise on the Pāramīs by Acāriya Dhammapāla as my guide.

I wondered, as I prepared the chart, whether it would work as a “flow-sheet” in chemistry, with one quality in fact conditioning the next in a way that seemed natural. My sense is that each of the paramis really includes all of the others and can be restated using the characteristics of other paramis in their definition, that each parami is a hologram for the other nine.

The Buddha taught that generosity was the first of the paramis because most people have something they can relinquish. In the largest sense, generosity is not giving away material things. It is non-clinging. As you can see in the chart, the proximal cause of generosity is seeing what can be relinquished.

For myself, giving up attachment to ideas, attachment to views, has been a much more difficult challenge than giving away material things. When I have been able to give up my attachment to views, it has seemed like an act of generosity both to myself and to others.

I’ve been able to give up views when I’ve recognized that I didn’t need them to protect my sense of self. In fact, they are easier to give up when I see that attachment to views constructs a sense of separate self and adds to my suffering. Students of the Zen teacher Seung Sahn report that he often said, “Only keep Don’t-Know Mind.” Another teacher of mine once said that a helpful mantra to be recited daily by anyone who teaches is “I could be wrong.”

I think another manifestation of generosity is giving up destructive habits or lingering grudges. In moments of clear seeing, which come through practice and perhaps by grace, we understand that anything we hold onto, whether material or emotional, is a potential source of complication and of suffering. With that understanding, generosity becomes easy.

Every moment of mindfulness is a moment of truthfulness

Morality is the second of the paramis. The commentarial tradition says morality has a composing effect. The practice of morality steadies and balances the mind and allows it to see clearly. Seeing clearly, we know that there’s a tremendous amount of inevitable pain that is part of life experience, and the impulse to respond with impeccable morality, to not add further pain to the inevitable discomfort of life, becomes spontaneous.

The parami of renunciation is often thought of as giving up something tangible in life. In Buddhist scripture it is usually to describe renouncing the world and joining the Order of monks and nuns. I find it more helpful to think of renouncing the habitual patterns of mind that keep me enslaved more than renouncing a particular lifestyle. Perhaps that’s because at those times in my life when I have needed to make a choice in terms of a more skillful lifestyle or habit, my experience has been that my strong decision to make a change made the actual changing fairly easy. It’s been much harder for me to change the habits of my heart.

It’s not easy to stay balanced. The mind’s habitual response to pleasant stimulus is to grasp it; its habitual response to unpleasant experience is aversion. Neutral moments are not so interesting, and we tend to stop paying attention to them.

I feared in the beginning of my practice that things wouldn’t feel as good or taste as good or sound as good or anything else as good, because a lot of the practice stories I heard talked about extinguishing lust. I still experience lust. And, while renunciation means to me giving up outbursts of anger in favor of a more considered, helpful response, I still recognize when I am annoyed.

I believe that renunciation is more a question of not being bound by or being a victim of the lusts and desires and angers that naturally arise as the result of having a body. I believe this is the difference between a compulsion or an addiction, which is always burdensome, and the possibility of making conscious choices, which is not burdensome. I don’t see renunciation as the difference between monastic and non-monastic lifestyles, but between being a victim of mind states, driven by compulsions, and being free to make a choice.

Restraint is a characteristic of renunciation. I remember Joseph Goldstein, one of my teachers and my friend, saying that restraint allowed for the verification of the empty nature of sense desire. In thinking about restraint, the most mundane example comes to mind.

I receive lots of mail order catalogs. Probably you do, too. My first thought often is, “No, I don’t need anything.” But the catalogs have interesting covers, and sometimes I think, “Well, I’ll just look inside.” Not infrequently, when I look through a catalog, I find something in it that I didn’t want or need two minutes before. In the moment of discovering it, and noticing that it’s attractive, I suddenly feel that I want it.

I think that it’s the nature of the mind to move toward pleasant experience in a grasping way. It’s not my hope for myself that my practice will lead me to a time that there is no movement of my mind toward things that are pleasant. What I hope will happen is that I will never be driven or compelled by wanting. In the matter of catalogs, my rule for myself is not to make a decision in the midst of a moment of lust.

Restraint allows for the verification of the empty nature of sense desire.

Wisdom is the fourth of the paramis, and its characteristic is clarity. Clarity seems the naturally developing result of restraint. When the movements of the mind in greed, hatred and delusion are fueled by stories—”I need this.” “I don’t like this.” “This is boring.”—truly clear seeing is not possible. When the movements of the attention, fueled by stories, are attenuated by the capacity for restraint, clarity emerges.

Validating for oneself the third noble truth of the Buddha, that peace is possible in this very life, requires only one moment of personal experience. If a moment is free, it’s free; if there is suffering, there is suffering. The clarity to recognize freedom, even a moment of freedom, can lead to faith that becomes unshakable. Otherwise it’s just hearsay.

In a moment of clear awareness we recognize the pain in our life and realize that we have the capacity to manage it. It’s a great liberation to know that you don’t need to be pleased in order to be happy. I think this is what leads to energy. On the chart you’ll notice that a characteristic of energy is indefatigability. I don’t think that means that you never get tired—I think it means resoluteness and dedication to practice.

I once heard a story about Chogyam Trungpa, that he classically would say to students at the end of the first day of retreat practice, “I’m sure that many of you would now like to go home.” Then he would laugh, and he’d say, “Too late.”

I think that there’s a point at which each of us begins to intuit that there’s a way to live life more gracefully and more peacefully. I think there’s another point, very important in developing practice, when we experience that possibility for ourselves.

Patience is the next of the paramis. One way to think about patience is reflecting on the ability to wait when anger arises in the mind. Lots of things make us angry. Often we feel the victim of something, and, especially when we feel we’re unjustly a victim, a lot of energy comes up around righteous indignation. Patience allows us to wait until the cloud of anger, which distorts the mind, subsides so we can decide on appropriate action. I once heard someone ask of the Dalai Lama, “Do you ever get angry?” He responded, “Of course. Things happen. They’re not what you wanted to have happen; anger arises. But it’s not a problem.”

On another occasion, the Dalai Lama was teaching about patience, using as his text Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life. He read each verse of Chapter 6 (the chapter on Patience)—134 verses—and commented on each one. Each verse proposed different situations in which anger arises in the mind and proposed appropriate responses. As the Dalai Lama read the last verse he leaned forward and held his head. Since my principal hindrance is worry, I thought, “Oh dear, something has happened to him.” Then he picked up his head, and I saw that he was crying. Since I know he’s taught this chapter and verse many times, I was touched by how much it obviously moved him to say that any response to vexation other than patience is unwise. Just unwise. If we have the patience to wait, waiting leads to clarity, and clarity allows for the truth of the situation to emerge.

The next parami is truthfulness. Every moment of mindfulness is a moment of truthfulness, of directed knowing. Direct and clear, true understanding is such a relief. It inspires determination in practice. And when we see the truth of how things are, our capacity for loving-kindness, for mettā, increases. We see people just the way they are—as people, like ourselves, struggling to be content, to be happy, to live gracefully—not as people about whom we have substantive commentaries that put them in categories of friends or enemies. As we become less judgmental and more tolerant, more able to understand that things and people are the way they are as a result of complex and legitimate causes, our capacity for balanced equanimity increases.

In choosing one story, in the service of creating an edited version of a whole day’s teaching on the paramis, here is a story that combines the capacity for seeing the truth, the determination to tell the truth, a moment of genuine metta, and the joy of equanimity.

About a year ago, I was fortunate to be part of a group of twenty-six Western teachers of Buddhism who went to Dharamsala to meet with the Dalai Lama. A trip to India is difficult under any circumstances, and Dharamsala is harder than Delhi. Nevertheless, this was a trip I would not have missed. I was excited about meeting with the Dalai Lama and excited to meet the twenty-five other teachers.

Our group of teachers gathered for several days before the meetings with the Dalai Lama to establish the agenda for our time with him. I knew perhaps half of the other teachers and only some of them well. At the start I noted that there were really three categories of people there: people I knew quite well and liked, people I didn’t know at all, and a few people I knew but didn’t have a good feeling about. For various reasons, all in the past, I had been negatively affected by these persons in some way. But, here we were far away, all of us with high alertness.

On our first day of meeting together, my friend Jack Kornfield who was the facilitator, said, “Let’s go around the room and introduce ourselves. Each of us will say our names and what we see as our current and greatest spiritual challenge in our personal lives and in our teaching lives.” I thought “This is a most intimate question to respond to in a group of twenty-six people, most of whom I don’t know.” But, I couldn’t leave, I couldn’t say, “I’ve decided not to come to Dharamsala.” I didn’t even have to make a decision about when to talk because Jack said, “I’ll go first, I’ll pass the microphone around and everyone will go in order.” I had the same feeling that I have half-way down a ski slope, or in a dentist chair mid-way through a complicated procedure, or, indeed, in the middle of life: “There’s no place to go but forward.”

In the clarity of that realization, my mind relaxed, and I listened. Each person’s story seemed touching to me—everyone told the truth about his or her current struggle. By and by, the people I had negative feelings about told their stories as well, and I discovered that I felt the same about them as about the people before and after them. My mind was clear and focused. I was relaxed. I wasn’t adding to that experience all the stories I had in my memory bank. I was seeing everyone just as they were. It was a tremendous relief. My insight that we are all, after all, just doing our best with the circumstances of our lives to manage gracefully, authentically and with integrity had a transformative effect. Everyone became my friend. And I felt a friend to everyone.

It’s a great liberation to know that you don’t need to be pleased in order to be happy.

I think that equanimity, the last of the paramis, is the ability to feel and understand, in wisdom, that everyone and everything is different, legitimately, as a result of different causes. To live in a friendly, non-adversarial relationship with all things, with all people, and with our lives is the source of greatest equanimity.