Many of the key questions scientists will be trying to answer in this century revolve around the mind and its relation to other entities. Is the mind the brain? Is the mind the body? Is the mind the body in the environment? Or is the mind some abstract entity that lives outside space and time altogether? I believe that Buddhist philosophy can help the process of reconciling these issues.

Science is based on the assumption that there is a single “real” reality that we each see through different lenses. If there is no systematic correlation between the state of the world and what we are measuring, there would not be much point in doing science. Quantum mechanics, of course, shows that what and how we measure are much more complicated than we ever thought. Newtonian scientists can describe the motion of the planets, or how to avoid being eaten by a lion. But reality, as it turns out, is far more complicated than that.

This has made the study of the mind particularly challenging. For science, of course, the first question before you begin to study something is to define what it is. But cognitive science—the branch of science particularly interested in understanding the mind and the nature of consciousness—is still struggling to define the mind and the brain and how they relate to each other.

There is a tradition within cognitive science that treats the mind as an abstract kind of entity. It says there is something about concepts and percepts that is somehow divorced from the world of matter. When people say the mind or the soul is somehow utterly unlike the body, they are not always doing it for purely dogmatic reasons. Whether you approach it from Buddhism, science, Freudian psychology, or cognitive psychology, the fact remains that there is a disconnect between the way we experience our lives from the inside and the way both ancient and modern sciences describe the nature of reality.

Classical Western science says that the objective point of view is the key. Look at all the objects that appear to exist without any subjects to experience them. All the subjective beings we know about appear to be only a tiny fraction of everything that is: The history of life on this planet is so small, on a world peripheral to a solar system on the edge of the Milky Way, one galaxy of about 100 billion in the observable universe!

If you take the mind and the body as two poles, the biological and neurological sciences have progressed very far in the understanding of the body as matter. Meanwhile the newer cognitive science, which comes from a tradition in which the mind is an abstract entity that does not necessarily have anything to do with brains or bodies or physics—or even matter in any form—has also gone some distance in understanding the mind as mind. But the conflation of the two, which is standard practice, is unskillful.

To give you an idea of how far apart traditional science and cognitive science are, for example, consider that science wants to know first of all where a phenomenon is taking place before studying it. I’ve had some serious arguments with other scientists over just that issue. Where exactly is the mind, they want to know.

Cognitive scientists observe certain regularities in human behavior that aren’t easily explained. Children, for example, learn certain language categories in ways we don’t understand. A child learns “dog” and can pick out other four-legged creatures that fit the category. Any mistakes, such as thinking a skunk is a dog, are quickly corrected. This is quite remarkable.

This is the same sort of phenomenon that the philosopher, cognitive scientist and linguist Noam Chomsky and others say argues for innate knowledge of language in humans. If this is really true, it runs into a hard problem concerning the mind/brain interface. If there are genes that encode this abstract knowledge, such as “dogs have four legs,” then there must be a category, “dogs,” that is independent of space and time. How can that happen? The structure of this knowledge is so different from anything else biology produces. We don’t understand how that can happen.

While the traditional approach of the materialist scientist works from the premise that third-person points of view, exemplified by classical experimentation, are the only way to find these things out, there have been some more recent movements to modify this. People like Francisco Varela, Richard Davidson, and Alan Wallace have advocated what is sometimes called neurophenomenology, wherein the first-person subjective reports of experienced meditators are compared with the data generated by such third-person techniques as fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging—brain scans). This is on the right track, but it seems to me these two frames of reference are so far apart that bringing them together is a much harder problem than neurophenomonology imagines.

Chomsky says our understanding of these things is similar to where physics and chemistry were in the nineteenth century. Chemists were discovering regularities in chemical reactions that seemed to relate to Mendeleyev’s periodic table of the elements. But the physicists of the day said that these could not be right, based on what physics understood at the time. But it turned out that it was physics that needed to change, not chemistry. It was not until the period between the 1930s and the 1950s that physics went through its own internal explosions and the chemical facts could get integrated. In the first sutta in the Majjhima Nikāya (Middle Length Discourses), the Mūlaparayāya Sutta, “the root of all things,” the Buddha compares the understanding of an “untaught, ordinary” person (one without practice in his teachings) with that of “a bhikkhu in higher training.” The untaught person “perceives earth as earth,” and then “conceives earth to be ‘mine.'” This might be seen as the same as the materialist scientist’s point of view. (Let’s not assume all scientists are strict materialists.) The “bhikkhu in higher training,” however, “having directly known earth as earth, … should not conceive himself as earth.” But he also should not “conceive himself apart from earth.” The Buddha seems to be saying that the truth is somewhere between these two points of view, and that clinging to either point of view will prevent us from seeing things as they are.

So how do we find the truth between “the mind is the mind” and “the brain is the brain”? I would like to show that Buddhist philosophy offers a glue to hold these two approaches together. Perhaps the psychological virtue pointed out by the Buddha in the Mūlaparayāya Sutta, to see clearly but not become identified with what we see, can also be an intellectual virtue, not being identified with one side of the issue or the other. This is what I mean by Buddhist philosophy allowing us a way to hold both extreme views of this issue at once without identifying with either one. Ultimately, of course, we want to take those technical insights from both Buddhism and cognitive science and see how they can inform our own lives.

Buddhist epistemology

I think Buddhist understanding of how we know what we know—what philosophers call epistemology—can help us here, at least as far as using this understanding in our daily lives is concerned. Not only are our brains capable of making distinctions such as “true” and “false,” our minds operate as “normative” entities, that is, we also have senses of right and wrong, beautiful and ugly, and so on, that operate in parallel. We are not just physical creatures, but are also evaluative creatures. We experience our bodies as fleshy things that have desires. Chomsky said that the reason the mind/body problem is so difficult is not because of the mind but because we do not understand what the body is. Desires are not just in our heads.

A Buddhist intellectual virtue can allow us to hold all this is in a useful way. It suggests that maybe the origin of the mind/body problem lies in trying to constitute two worlds as given in the first place. This separation is a relatively new idea. It was not taken for granted in either ancient India or ancient Greece. Its most extreme form comes to us through the Christian Scholastic tradition, which rediscovered ancient Greek ideas but wanted to make them coexist with Christian spiritual teachings. The solution, in a nutshell, was to separate the realm of the spirit from the material realm, so the emerging realities of science didn’t conflict with the teachings of the religious authorities. Science stayed on the material side of the line; human consciousness, free will, and so on, on the other side.

Maybe the origin of the mind-body problem lies in trying to constitute two worlds as given in the first place

The Buddhist notion of conditioned experience proves helpful here. Our experience in saṃsāra is driven by karma, or volition. Our volitional actions lead to desires, which in turn cause suffering—in fact, our whole experience. This is very different from a modern material-only world driven by impersonal physical forces. Karmic theory is also impersonal in the sense that it doesn’t depend on you or me as individuals; it is only the working out of conditions, even though it can be influenced by our intentions. This intentionality can be thought of as embedded in a material world.

In the Buddhist view, we are conditioned beings in saṃsāra, where dukkha is part of the furniture of the universe, if you will. But dukkha, suffering, our everyday experience, is neither exclusively subjective nor objective. It is not either just material or just mental. This is central to the mind/body problem; it is saying that concepts appearing to fall squarely on the mind side or the body side can actually be somewhere in the middle—the middle way.

To be human is to be conditioned this way, and cognitive science has a hard time accepting its own discoveries about this. If we combine this with the Buddhist idea of the lack of a substantial self, then any existence in any form whatsoever implies that it is conditioned. That yields fresh insight into the mind/body problem.

Accepting exceptions

But back to the other extreme position, that the world of human experience is not the universe as a whole. We have to work with that, without getting rid of the livingness of the world we know or making outlandish claims that even atoms and molecules are sentient. This is really tough, and I think the model that we should adopt is the situation with chemistry in the nineteenth century. We start with the living human world in front of us, which is what cognitive science and biology do. We also know a lot about the mind; we just don’t know how to make that consistent with what we know about matter.

One possibility is that the mind in its empirical manifestation—that is, the actual human behavior, not the idealized mind of the extreme material position—just is not how we think it is. It does not operate by theories of logic. So even though we think “dogs have four legs,” we are willing to accept that it is not true of every dog. Logic has a problem with that, but we do not, really.

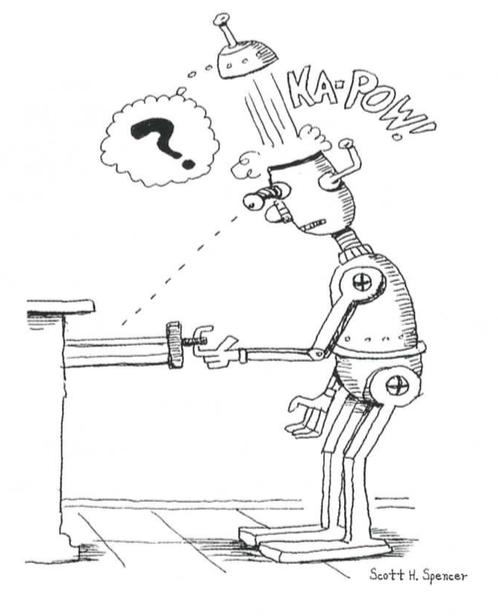

Common sense, as opposed to scientific notions, has always been willing to accept exceptions. That’s just the way it is. We arrange things in our kitchen drawer in some logical way, with knives here, forks over there. But if one day a knife ends up somewhere else, our heads don’t explode. A robot, on the other hand, programmed to find a knife in a certain place, would be stymied if it couldn’t find it there.

A living organism trades off faulty behavior for robustness. We know to stay away from tigers, but we also have cognitive space to sense new dangers and avoid those too. Human beings evolved to be open-ended thinkers because that helped ensure survival. The scientific method, on the other hand, is designed to change slowly and eliminate exceptions—all outcomes must be predicted or the theory is wrong.

A living organism trades off faulty behavior for robustness. We know to stay away from tigers, but we also have cognitive space to sense new dangers and avoid those too. Human beings evolved to be open-ended thinkers because that helped ensure survival. The scientific method, on the other hand, is designed to change slowly and eliminate exceptions—all outcomes must be predicted or the theory is wrong.

Embracing opposites

Cognitive science began as a reaction to the behaviorism that psychology had become following the rise of Newtonian science. Living things were treated as black boxes: inputs and outputs were all that mattered. As such, cognitive science is already a step toward a Buddhist science of mind from where we were fifty years ago. But cognitive science has also gone to the other extreme, saying that mental activity is reasoning and abstract functioning, and that is fundamentally immaterial. Buddhism is a placeholder, at least, between those extremes.

Continuing with the idea that our problem starts with conceiving different worlds, consider how cognition is embodied in our language. Words like “left” and “right,” “in front of” and “behind,” have meaning only in relation to our bodies. We are conditioned as beings with two arms, two legs, a front and a back, and this shows up in our cognitive acts. Things are very different for a fish, for instance, whose eyes look only to the sides.

So it’s not as if mental activity is in a layer that happens in this special region called the brain that is somehow grafted onto our bodies. A cup has meaning to us because of how we see it and pick it up with our bodies. To an ant, it’s probably just a large rock. Our immune systems key on certain chemical signatures of bacteria; our visual systems do not. You could argue that our immune systems perform a certain kind of cognitive act; they know something.

All these individual pieces of the cognitive puzzle can add up to a process we call a conventional self in Buddhism, recognizing that it has no ultimate essence, that it’s just a collection of processes. Going back to intentions, we know it’s absolutely crucial for the Buddhist framework that intentions are part of the human world. We don’t need to decide whether collectively they have some ultimate purpose. Each intention creates its karma; there’s no universal accountant keeping track of it all. The morally complex ecosystems we see are simply the result of individual forces working themselves out.

In the Western scientific tradition, you can have patterns that humans impose on the world due to the kind of beings we are (what our senses are capable of, for instance), and you can have patterns that “seem to really be there.” For science, they must be one or the other. But Dependent Arising in the Buddhist analysis implies that all these patterns are both just out there and also just arising in our minds when we observe them; they are all co-conditioned. Once again, science wants to force a choice where Buddhism is content to hold all things at once.

My claim is that the Buddhist path is generalized, not just subjective. If scientists can learn to be reflective about their intellectual practice—Buddhism as an intellectual virtue—they can be better scientists. And the general message for all of us is that we shouldn’t take those aspects of human life as somehow separate from our personal lives. The Buddha’s message applies to all domains of human behavior.

A new cognitive science

The newest developments in cognitive science go by the name embodied cognition. Some of the leading thinkers, such as Varela, were influenced by Buddhist thought, but the ideas can be described in purely scientific terms. These theories try to bridge the gap between body and mind. Embodied cognition assumes that the only way we can be cognitive beings is because we have certain kinds of bodies.

Consider perception. The dis-embodied cognitive theory would say there is a soul (or some essential thing like that) in your head that gets input from the world and faithfully represents it. This is the pinhole-camera view of perception. The purpose of sensation and perception is to recover the exact shape of the object. David Marr, who is in some sense my intellectual ancestor, wrote the classic book on this approach, in which he said “vision is the process of knowing what is where by looking.”

While this sounds straightforward, in practice it’s a very hard problem. Take the simple image of two parallel lines. According to the theory, light impinges on your retina in a certain way such that you can use the photons to recover the shape and location of the lines. But there are an infinite number of different positions in the world of two lines relative to each other that give the same projection on the retina.

The way we solve this problem is that we move. Because things that are farther away from us move more slowly than things that are closer (a phenomenon called motion parallax), we can correctly interpret, for example, whether two objects are on the same plane.

Marr and others showed how we need these additional hard-wired constraints to interpret the world accurately. Despite this, embodied cognitive scientists say we’re still not as good at representing the world as we think we are. The pinhole-camera model assumes we can look out and get a 3-D, enriched Technicolor representation. But many experiments show were not doing that at all. Change blindness is one well-known example. You can show subjects an image and ask them to press a lever when they notice a change. But it turns out that some seemingly obvious changes, such as an image of an airplane whose wings slowly disappear, or a basket with an apple in it that changes color, aren’t immediately obvious to the viewer.

There’s no pure understanding of time which is independent of space.

So we just don’t have a constant, perfectly accurate view of things in our heads. In truth, we only need to know about where things are, just enough to know if we should get farther away from them or move in closer to pick them up. Movement gives us clues about what to do next.

If you think about it, this is perfectly consistent with the idea that we are evolved, conditioned beings. You do not need to know every detail of how to get from here to Boston. You know a few things, and the world gives you cues along the way, such as when to take the right exit. The entire highway map is not in your head.

Metaphor and the limits of thought

The ultimate implication of this for cognitive science is that there’s no such thing as pure free thought. The body limits our thought. We can’t think what it’s like to live in a seven-dimensional universe, for example, even though physicists have some math that shows there may be at least that many dimensions. Related to that is a very influential account of the nature of thought which says that a lot of thought is metaphorical.

Until relatively recently, thought was usually understood as a kind of reasoning, some form of “A implies B implies C, therefore A implies C.” George Lakoff and others have shown that while that sort of thinking is certainly real, most thought isn’t like that. Most thought is a kind of metaphorical free association.

We understand the world through metaphor, so we say, “time is like a river.” That’s actually the only way we can understand time. We don’t have a direct experience of time. We experience motion and change, and through metaphor we have an indirect experience of time. There are basically two kinds of time, or change, in our experience: motion, and growth and decay. Since time and space are so closely related for us, we have to spatialize time to understand it. It’s a strong claim, but there’s no pure understanding of time which is independent of space.

The more you look at everyday language, the more you see metaphors at work. We say “the salesman pressured me into buying the car,” the same language we would use for a physical process. The same cognitive architecture describes mental processes and physical processes.

It’s as if we are intuitively Buddhists: Intellectually, we want to make this distinction between matter purely as matter and social, emotional, experiential events as purely consciousness. But the way we talk and perceive and reason in the world is by intuitively packaging the two together—it’s built into the structure of our minds.

This is a very strong claim. It’s saying our common sense packages our mind and body together. We may speak of the two as if they’re separate from time to time, depending on the metaphor we’re using, but unconsciously things are mostly very different from that. The metaphors that experts such as scientists use to clearly separate mind and body are secondary metaphors, according to this point of view.

But we live in a culture increasingly influenced by metaphors that come from science. Once we’ve got these in our cultural DNA, it might take years of sitting meditation to sort out their effects from our thoughts!

Of course, it may turn out to be a fad, using ideas from Buddhism to point toward a solution to the mind/body problem. On the other hand, progress in the mind sciences will be one of the most important areas for science during the entire twenty-first century. These ideas are important enough that they should be known by scientists everywhere, regardless of what is eventually done with them. If somebody’s able to make a strong case as to why we should take the middle path as a general attitude toward the mind/body problem and not get attached to one extreme or the other, we may actually end up making tremendous progress.

Rajesh Kasturirangan is a faculty member at the National Institute of Advanced Studies at Bangalore, India. He has a doctorate in cognitive science from MIT. This article is based on a course he taught at BCBS in May 2009.