These words are extracted from a course offered by Joanna at BCBS in October, 2000.

In every tradition, the spiritual journey seems to be presented in two ways. One is like a journey out of this messy, broken, imperfect world of suffering, into a sacred realm of eternal light. At the same time, within the same tradition, the spiritual journey is also experienced and expressed as going right into the heart of the world—into this world of suffering and brokenness and imperfection—to discover the sacred.

In every tradition, the spiritual journey seems to be presented in two ways. One is like a journey out of this messy, broken, imperfect world of suffering, into a sacred realm of eternal light. At the same time, within the same tradition, the spiritual journey is also experienced and expressed as going right into the heart of the world—into this world of suffering and brokenness and imperfection—to discover the sacred.

The second half of the 20th century has witnessed a move to reclaim the journey into the heart of the world. We are still grateful for the traditional vertical dimension, the upward trajectory into realms of bliss and timelessness, the movement from the dark into the light, from the profane to the sacred, from matter into pure mind. But in our time that ascending movement is counterbalanced by a more horizontal thrust, or even a descent, to enter fully the world as it is, to know its own beauty and its suffering. As can be seen in a plethora of books and teachings, there’s a strong yearning in our time to resacralize ordinary life.

All over the world I see people risking their comforts, risking their jobs and sometimes their lives, to act on behalf of other beings and to protect the living body of Earth. They put themselves in service to the broken and the dispossessed. And among these activists the hunger for a spiritual understanding of what they’re doing, and for spiritual practices to strengthen them, seems to be growing by the week, the day, the hour. Their confrontation with suffering feeds their search for awakening—for freedom from the obscurations and obsessions of the separated self, for liberation from greed, hatred, and delusion. This kind of liberation takes one not out of the world, but right into it! It is a release into action.

So I resonate with Carl Jung when he says that a central shift in our time is from seeing the spirituality as a journey toward perfection, to seeing it as a journey toward wholeness. To my mind, that changes everything. It even feels like a different posture. Instead of holding aloof from travail to clutch and climb up a ladder to the sacred, the movement is to open the arms and embrace it right here.

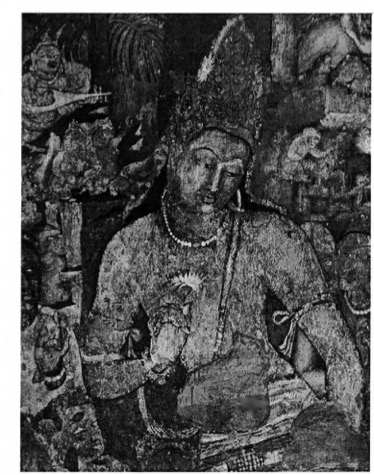

In Buddhist history, this movement into the heart of the world is associated with the bodhisattva. In early, Theravada, Buddhism the term bodhisattva refers to the earlier lives of Gotama the Buddha. He had lots of them, and in each he practiced and grew in compassion and wisdom. These are the hallmarks of a bodhisattva: compassion and insight into the interconnectedness of all beings. And he developed those capacities not just in human lives, but also in non-human lives. Many of you probably share my delight in the Jataka stories, where these earlier lives, with wondrous displays of courage and compassion, are recounted. In some of them the Buddha was a rabbit, or a monkey, or an elephant, or a snake, as well as a merchant and a prince, and a counselor to kings.

As Mahāyāna Buddhism comes on the scene, the central doctrine of the Buddha, dependent co-arising, is understood with fresh appreciation and vigor. As that happens, a resounding recognition comes: “Oh, given that we course together in radical interconnectedness, we belong to each other. We are all bodhisattvas—that is our true nature.” That is a major message of the Perfection of Wisdom sutras which inaugurate the Mahāyāna.

As the tradition ripened over the centuries, archetypal forms of bodhisattvahood appeared, as celestial bodhisattvas. These you can call on at any time; they are right at hand. You honor your own capacity for wisdom, as you think of the celestial bodhisattva Manjushri, the embodiment of wisdom. Or you experience your own compassion, as you turn to the Compassionate One who listens, Avalokiteshvara. Or you access your own creativity and courage, as you turn to the bodhisattva of action, Samantabhadra. Or you discover your own fearlessness, as you turn to the bodhisattva Kshitigarbha, who’s not afraid to go down into the deepest level of hell for the sake of those who suffer there.

That’s the gift from these celestial bodhisattvas—to symbolize and evoke the capacities of the human heart and mind, to represent what we all want to expect of ourselves. As we learn to see ourselves and others as potential bodhisattvas, we find more equanimity in our relationship to our world—not to be scared of the messiness and the pain; not to hold back and close off from the world. Instead we open up and move into it. So there’s both fearlessness, and a kind of celebration.

Bodhisattva behavior is actually present in all schools of Buddhism. It abounds in Theravada, the Way of the Elders. Though the term is not used there, bodhisattva behavior is clearly manifest and called forth. I discovered that when I went to live in Sri Lanka, a Theravadan country, and work with the Sarvodaya movement, a Buddhist-inspired community development movement active in thousands of villages.

In my first year with Sarvodaya, I went through trainings for village workers. The trainings included more than regulations for development loans, or ways to organize village councils, or how deep the latrines should be dug. They included the practices of mettā, karunā, muditā, and upekkhā, the four abodes or Brahmaviharas. We learned to practice loving-kindness, compassion, joy in the joy of others, and equanimity, and see them as resources for social change. These are clearly bodhisattva tools for being in the heart of the world.

As a matter of fact, that is how these practices arose. A group of Brahmins came to the Buddha and asked him, “How do you, honored teacher, assure that the self, the atman, gets to heaven, the Brahmaloka?” They thought they could nail him on that one, because he was known to be both agnostic and averse to rituals. But the Buddha was a clever one. He didn’t say, “Well actually I don’t approve of rituals”—which he didn’t, because they were quite costly and bloody at the time. And neither did he say, “Well actually I’m not sure there is a god in heaven.” He just said, “You want to know, I’ll tell you.” And he taught the divine abodes, the practices of mettā, karunā, muditā, and upekkhā, which take you to the heart of reality. Then, for all intents and purposes, you are in heaven. You practice that loving kindness; you look at everyone with those eyes of compassion and joy and equanimity, and there’s nowhere else to go. You’re home.

So the path into the heart of the world can be found throughout the Buddha Dharma. In the last half century there has been such a stirring for what Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh first called “Engaged Buddhism,” that some have wondered whether this might be a new path in the evolution of Buddhism. At any rate that’s what Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the great leader of the untouchables in India, said forty-five years ago in India, when he converted to Buddhism along with half a million of his people. He said this event would launch a new vehicle, the “Nava-yana,” wherein we enact the practicality of the Buddha’s teachings for our whole lives. The ways we treat each other, the respect and freedom that we accord one another, are central to this Navayana.

*

What does all this mean for us in our own lives? What are the ways we can live in the world as a bodhisattva, entering freely and fully into the heart of things, staying sturdy and strong in the midst of the turmoil? The gifts of the bodhisattva are many, and a crucial one is simply sharing presence. It is the gift of being fully here, with eyes and ears open, not wishing you were somewhere else or comparing it to a place you prefer to be. It is being in the world as it is. With each passing year I believe more strongly that this is the greatest offering we can make: our presence. Not our smarts, not some great plan or strategy, not even our generosity and serenity—but our sheer, irreplaceable presence.

There is so much going on in our world today that makes us want to close down and not see and not hear. It’s easy to shut down in the face of suffering. But I think that’s the greatest danger of our time. The greatest peril is not nuclear war weapons, not climate change or the poisoning of seas and soil and air, not the impoverishment of more than half the world’s population, nor the murderous, genocidal wars flaring up. It is not the disappearance of cultures, or the extinction of species. The greatest danger is the deadening of our hearts and minds. It arises not from indifference, but from fear. We fear we can’t stand it, if we take it all in. We fear we might be shattered by pain, or stuck in despair forever.

It is in this context that I find the practice of vipassanā—simple, straight vipassanā—to be immeasurably valuable. I first learned it as satipaṭṭhāna, sheer  moment-by-moment mindfulness: using the breath; noticing when you go off, and then coming back; noting the arising of thoughts and mental objects, sensations and feelings. Just being present to them. You discover that you can sit there and be present to it all without having to approve of what comes up. It’s an act of courage and freedom to be present with something unconditionally, without referring to whether you like it or not. We need that to be present to our world.

moment-by-moment mindfulness: using the breath; noticing when you go off, and then coming back; noting the arising of thoughts and mental objects, sensations and feelings. Just being present to them. You discover that you can sit there and be present to it all without having to approve of what comes up. It’s an act of courage and freedom to be present with something unconditionally, without referring to whether you like it or not. We need that to be present to our world.

In courses I teach in Berkeley at the Graduate Theological Union, we study the condition of our world, read reports on the global ecological and social crisis; and for that reason I see to it that we also meditate. The students make a commitment to daily vipassanā practice to learn how to handle painful information. If you can be sturdily present to yourself with all the internal garbage that comes up in sitting practice, then you can be present to the facts of deforestation and species extinctions, and all the insanities happening to our world today. That unconditional presence is the first and essential act we must make. Simply to be there with open eyes, open ears, open heart. All else flows from that.

*

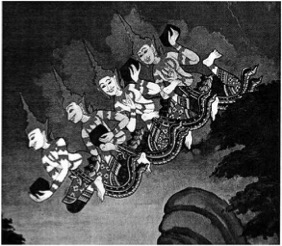

In the earliest Mahāyāna texts, the Perfection of Wisdom scriptures, the bodhisattva is portrayed as flying on two wings. These sutras explain at length that the bodhisattva doesn’t have any place to stand, because there is no turf, views or possessions that she can call her own. Nor is there a solid self, or an unchanging identity, or any security, as we understand security. What security can there be for the bodhisattva, if you take seriously the Buddha’s teaching of the nature of the self?

Well, the bodhisattva doesn’t need a place to stand because she or he flies—flies in the “deep space” of the Perfection of Wisdom. And the two wings on which the bodhisattva flies are compassion and wisdom. Instead of looking for a safe harbor, for a place where you’re all protected and cozy and safe, you just fly high on these two wings and place your trust in them.

Alan Watts talked about the wisdom of insecurity. He says when you try to capture water and hold on to it, it becomes stagnant. And so does life. But when you let the water flow, it remains sparkling and fresh. My own private mudra, to help me through the sorrow of leaving beloved people or places, is this: to open my fingers and imagine water running through them, sparkling and touching the light and staying fresh as it moved. In the Buddha’s teachings, that’s what we are, a stream of being, bhava-sota. And viññāna-sota, stream of consciousness. We are not a permanent, unchanging self; we flow like water, with no place to abide. So with no safe place to stand, the bodhisattva flies—flies on the wings of compassion and wisdom.

*

We need both of them: compassion and insight into the radical interdependence of all phenomena. One isn’t enough. We need the compassion because that openness to the pain of the world provides the fuel to move you out where you need to be, to do what you need to do. Yet compassion by itself, without understanding and trusting our interconnectedness, can burn you out. So you need the other wing, the wisdom that knows how interwoven we are in the web of life, inseparable from each other. That wisdom reminds us that we’re not involved in a battle between good guys and bad guys, for the line between good and evil runs through the landscape of every human heart. It teaches that we are so interconnected and inter-existing that even the smallest act with clear intention has repercussions throughout the web of life. But wisdom by itself is not enough to move us forward for the sake of all beings; it needs the steady, heart-opening beat of compassion. Then we fly.

Looking at the hand gestures of Tibetan monks as they chant, you see mudras portraying the dance of compassion and wisdom. In motion they interact. We can’t have one without the other. When we open to the pain of our world what we discover is our interconnectedness. And as we open to our mutual belonging, we feel the suffering. We don’t shut it out. So compassion and wisdom belong together, empowering each other. They are the two wings of the bodhisattva.