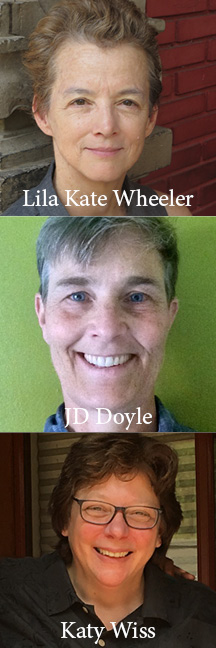

In December, Kate Lila Wheeler, Katy Wiss, and JD Doyle will be teaching a program at BCBS called “Taking Freedom to Extremes: Teachings for Responsible Social Action.” In this course they will explore the Buddha’s teachings as resources for responding to the challenges and complexities of our social and political lives. Insight Journal conducted the following interview with the teachers via email.

Insight Journal: Urgent and unprecedented challenges face human communities all over the world. The earth’s human societies and ecosystems are in crisis. Sincere people feel a call to help. What resources does the Buddhist tradition offer to encourage, guide, and support us?

Insight Journal: Urgent and unprecedented challenges face human communities all over the world. The earth’s human societies and ecosystems are in crisis. Sincere people feel a call to help. What resources does the Buddhist tradition offer to encourage, guide, and support us?

Lila Kate Wheeler, Katy Wiss, JD Doyle: First of all we’d like to say that Buddhists have been activists for thousands of years, beginning with the Buddha himself and on up until now when Engaged Buddhism is a theme all over the world, including in Asia. The Buddhist teaching is not to turn away from suffering, and to expect difficulty but to deal with conflict in a nonviolent, even a loving way. These key teachings underpin many justice-oriented movements. Extinction Rebellion is one example of a movement that takes Buddhist teachings seriously, including using meditation to help people cope with fear and anger and stay away from blame, understanding that we are all caught in toxic systems.

To be even more specific, Buddhists truly want to help free ourselves and others, and each Buddhist school has something to offer. Mindfulness, Insight, or Theravāda teachings orient us to freeing our minds and hearts as individuals, though we hold an orientation to loving all beings equally and may in some cases be urged to take action. Mahāyāna teachings orient even more to the collective. If we aren’t helping others along with ourselves, it isn’t Dharma. Many of us are familiar with the Bodhisattva vows, to enter spaces of suffering to liberate all beings. In Mahayana teachings self and other are interdependent so we are not really different. That means everyone “belongs” equally. Then the Vajrayāna teachings speak of the purity at the heart of all of life, the innate enlightenment of beings. And all of the traditions suggest developing loving kindness and compassion, to feel more strength, gentleness, and buoyancy, so that we don’t revert into rage, uncaring or despair. At this retreat we’ll explore aspects of all three approaches, though the main texts will be Theravadin suttas, said to be spoken by the Buddha himself.

Another crucial thing for us to know about, as contemplative activists, is that there are not only teachings but precedents for Buddhists to engage in balancing contemplative practice with outward engagement and nonviolent resistance – beginning with the Buddha who sat under a Bodhi tree to become enlightened, but later sat down in the path of an invading army three times, and tried to persuade them to stop. We are going to explore several teachings from the Buddha that show he’s acutely aware of the same outer issues that call our attention today – oppression, class and wealth.

IJ: What inspires you to teach this course?

LKW, KW, JDD: Our course, Taking Freedom to Extremes, was born from the passion of three teachers who are activist/meditators. JD is gender nonconforming and Katy holds lesbian and disabled identities. Lila is coordinating the current, highly diverse, retreat teacher training at Spirit Rock along with Larry Yang and Gina Sharpe, a form of activism within the Buddhist community. The three of us were excited to discover elements in the two suttas, offered as the principal texts for this program, that seem to be overlooked. One sutta could define our deepest orientation as nonviolence. The other sutta is an instruction from the Buddha on conflict, and what to do when it arises. Should we do something, speak out? Or let go? The instruction isn’t always to let go.

Our course title, Taking Freedom To Extremes, is intended with a touch of humor derived from the Buddha’s own. The sense of extreme nonviolence comes from our first text, the Kakacūpama Sutta. It’s a lengthy sutta that begins with a monk getting upset when the women monastics were insulted. The Buddha’s response to this monk seems to indicate that the monk was not simply being protective of them as a male ‘ally’ of women but perhaps hanging around with the nuns for unwholesome reasons. We will be interested to know what retreatants think about this, and what it may reveal about our own vision of the world! The sutta includes the Simile of the Saw, which is often quoted at loving-kindness retreats.

“Even if a person is being cut in half with a two handled saw, if they give rise to a thought of revenge, they are not following (the Buddhist) teaching.”

That image sounds extreme. Impossible. Undesirable.

But did the Buddha actually intend us to let ourselves be sawn in half? He may have been making his point in a dramatic and humorous way, forcing the listener into a reaction. Deeper inquiry is warranted and that’s what we will invite retreatants to do. There may be no final answer, except that the saw image, along with other aspects of the Sutta, points to a deeply nonviolent view. If we undertake social action without implicitly or explicitly invoking revenge or blame, without fueling anger inside our hearts, could this be the regenerative approach many activists yearn for?

As we examine the Kakacūpama Sutta as a whole, we also find one of the Buddha’s creative fictions, a parable to illustrate his points. As teachers, we don’t want to say too much here so that participants discover the sutta for themselves. The sutta has many intriguing aspects –like how the Buddha understood that resistance strategy can be used by a powerless slave with dark skin, whose intelligence he respected, it seems, since she was the wisdom-bringer in the sutta.

IJ: What is the other sutta you will be exploring? What guidance might it offer for someone inspired by Buddhist traditions to address contemporary social challenges?

LKW, KW, JDD: The second sutta, Kinti Sutta or What Do You Think of Me? must have been offered after some monastic squabble! The Buddha calls his students together and says, perhaps wearily, “Why do you think I’m doing this? Do you think I’m into the free food? Or the glory of the robes?” (Which were made of rags, so he is probably being sarcastic). He goes on from there, exhorting the monks to engage with others who cause division, even when it’s hard to do even if they feel uncomfortable, or know they are making the other person uncomfortable. We can derive a decision-making matrix from this sutta since the Buddha is very clear on when it’s helpful to take action and when not to. Whether it’s troublesome is not one of the criteria. So if we want to follow the Buddha’s instruction, we will speak out even when it’s hard for us and hard for the other person, as long as we believe it’s possible that we’ll get our message across.

IJ: There is conflict in both of these suttas. What do you think these texts can teach us about conflict and how to address it skillfully?

LKW, KW, JDD: Both suttas acknowledge that conflicts will arise and often, they’re not easily resolved. This brings us full circle to the need to live – well – with  uncertainty and failure. Whether we are hoping to save a forest or a people or a planet – or even just live our life and strive for happiness as harmlessly as we can – this world will always carry a quotient of sufferings. We may not achieve our goals. We have to learn how to do our best and then let go.

uncertainty and failure. Whether we are hoping to save a forest or a people or a planet – or even just live our life and strive for happiness as harmlessly as we can – this world will always carry a quotient of sufferings. We may not achieve our goals. We have to learn how to do our best and then let go.

So for this retreat, we will offer some of the powerful internal meditative ‘technologies’ used in the Insight and Theravāda traditions. These guide us to awareness of what’s going on inside us and help us to develop a more compassionate awareness toward anger, fear, greed, despair and self-righteousness. How can we release the grip of these unhealthy states? Knowing how to ease off when our own mind and heart fill up with conflict may not happen on its own, including the internalized sufferings we may feel empathically for others whose sufferings we don’t know how to relieve. We don’t want to retreat into a bubble, either. Skills of being present, and kind also help us to recognize and release places where we are caught in habits and rumination. Getting unstuck may not require a long developmental process. We’ll do our best to present methods for getting unstuck relatively quickly. Our approach to mindfulness is trauma-informed, though, which means we will invite you to engage with our practices, but encourage and support you to find your own responses. All of our instructions are offered as supports, but there is no one way that works for every person. Especially when we ask ourselves the question: what is my responsibility? How shall I live? It’s so important to be authentic in exploring and finding our path. Yet exploring together with each other is tremendously important, too. We cannot do this alone.

IJ: It seems that you hear a Buddha speaking in these texts who is committed to a practice of liberating oneself from unwholesome states, such as anger, and is simultaneously very much a socially engaged Buddha.

LKW, KW, JDD: Yes. It seems clear to most of us that in our collective situation now, changing our personal internal reality isn’t going to be enough. As teachers we are excited to bring alive, or so it seems to us, a Buddha who was not just advocating withdrawal from ‘the world’ into a bubble of meditative comfort, self-improvement, or the depths of spiritual liberation. Self care is crucial but Buddhist practice goes beyond that. As a teacher the Buddha clearly advocates mindfulness of others’ minds and hearts as well as our own. We see him as acutely aware of class, privilege, and what we call now the ‘fragility’ of those who are accustomed to having power over others. The Buddha subverted class and privilege when he ducked out of being a king and renounced his power. He directly invited his personal students to nonviolent engagement to change others’ minds. He remained calm and compassionate, generously teaching even when students weren’t able to do what he said. This Buddha inspires us to offer service as best we can in a regenerative way, including activism and contemplation.

IJ: What are your intentions for this program at BCBS?

LKW, KW, JDD: We hope everyone will come away feeling a clearer sense of how to direct our desire to truly help ourselves and others The course material is ourselves as humans in this day and time. Each of us engages with our inner and outer worlds differently. As practitioners, we can learn from each other and from the texts and teachings, and from the practice of going within to see where we are caught and where we are free. We will reflect together on what it means to bring this ancient wisdom tradition into our contemporary world. Is it helpful or unhelpful? To what extent are we free to play with a tradition? Just as our outer world is represented inside our minds, the texts speak to us in our contemporary lives. Interpretation is always creative, but it requires integrity, too. We will engage closely and respectfully with the material. Many of us feel we haven’t done that enough, or not as deeply as we’d like. So this is an opportunity to do some study.

We will spend time as a group in silence, doing ‘cushion practice;’ we will read suttas together aloud and discuss them in small group format and larger-group collective conversations. The three teachers will offer guidance for structuring the conversations respectfully and safely. Supplemental texts and insights, and optional meditation interviews. Together, we’ll discover what emerges.