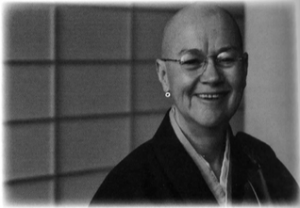

Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara is the abbot of the Village Zendo in Manhattan. She is a Soto Zen Priest and certified Zen Teacher in Maezumi Roshi’ White Plum lineage. She received priest ordination from Maezumi Roshi and Dharma Transmission from Bernie Tetsugen Glassman Roshi. She holds a Ph.D. in Media Ecology, and taught at NYU for twenty years.

One usually thinks of a Zen temple as tucked away peacefully in some fold of the misty mountains. I’m guessing this is not quite the case with you in Manhattan.

Precisely not! It reminds me of when a Zen teacher was asked how to enter the Buddha way, and he said, “Do you hear the sound of that stream? Enter there.” Our zendo, plunked down right on Broadway, a few dozen blocks from the old World Trade Center, enters the Buddha way through the sounds of sirens, church bells, the rumble of loading and unloading products and garbage. We occupy an old loft space on a high floor, and morning meditation is filled with sunlight from the east, a view of the eastern Manhattan skyline, and the sounds of the city waking up.

Finding quiet within this context definitely strengthens practice. We learn to drop our constant craving and aversion, to be present to what is—without reactivity. Then, when we go downstairs and reenter the streets, there’s plenty of opportunity to actualize compassion in every moment.

Why did you decide to establish a Zendo where and when you did?

Back in 1985, I was still teaching at NYU, with family responsibilities—a college-age son and an aging mother—and it seemed expedient to begin just where my life was. Initially, we were simply a sitting group, practicing in my apartment. Years passed, and we grew organically, in size and intention. As we grew, we just naturally evolved to meet the needs of where we are.

Are there any special challenges to operating in such an urban environment?

Perhaps the main challenge is to keep our awareness that every annoyance and irritation that we may attribute to our environment can be a skillful means for our practice. I think that ideally, in a rural environment, the natural world contains us, helps us to see our place in the arising and falling of each moment. Of course, if our mind is troubled, the rural environment can appear threatening, sad, or even anger-provoking! In an urban context, the same is true, the sounds and sights tend to be foreign, grating, industrial, and yet the mind can either make music and hear the spaces between or it can create suffering.

This fall, when I returned to the city from our annual five-week retreat in the country, the first thing I noticed was the marvelous beauty of the faces of the people walking down the street. They were like flowers, each one unique, so many colors and sizes, like a summer meadow.

How did you first get involved in Zen practice?

For me, it was the arts. As a young woman I was drawn to the spontaneity and freedom of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, Korean ceramics, and the poetry of the Zen tradition. Studying in Berkeley, I had access to wonderful collections of Asian art and literature. Going a little deeper, I discovered the Zen principles that gave rise to these forms, and I was hooked.

Who comes to your center and why?

I think people come because they are seeking themselves, seeking the meaning of their lives. A young man may come in order to find what he wants to do with his life. An older woman might want to find a way to make peace with herself before she dies. Of course, it is hard to make generalizations of who comes here. We have a good distribution of age, class and sexuality. We could do better in terms of race, and we are looking at that. There is a preponderance of artists, healers (therapists, health professionals, chaplains), and teachers. We aren’t real flashy. We sit a lot. We study koans, sutras and sastras.

Are you training people to be leaders in your tradition?

Oh yes. As I get older, leadership training becomes more urgent for me. Through the years I have seen the astonishing workings of the dharma in people’s lives. It seems to me that it is critical to pass on the teachings and teaching skills that I have absorbed from my excellent teachers and then let it out.

What does such training involve?

Trainees are encouraged to do as many of our residential retreats as possible, to study the dharma independently, and to do deep inquiry into their motivation. As a whole community, we do ongoing sutra and great writings study. We take a long time to develop teachers in our tradition. Many years. During that time, a Zen student usually has a private interview with me each week and, on retreat, each day. In these interviews we work on koans (old stories that point to vital aspects of the dharma) or we may discuss issues in the person’s life, or we may focus on the precepts. After a few years, the training includes giving meditation instruction to others, giving dharma talks, and being involved in the overall governance of the group.

Then they begin to give private interviews under my supervision. Some are at that stage now. Soon I will be giving final, independent teaching status to the first group.

Every annoyance can be skillful means for our practice.

What role are your trainees likely to play in their communities?

It depends on the situation. For example, one trainee heads an affiliate center, so she serves as an instructor, a counselor, and a priest. Another leads a group at Sing Sing prison. He offers instruction, services, and interviews. Other trainees are more involved with governance, chaplaincy, or center operations. A potter’s offering is very different from a scholar’s or a therapist’s. The trick is to give trainees enough space to develop their own unique teaching capabilities, and yet continue to offer them the support and structure of what I have inherited from my teachers and my life experience.

What would you say is the most valuable thing the perspective of Buddhist practice offers to, for example, a New Yorker fully engaged with a demanding set of duties and responsibilities?

Well, it’s about how to live. How to find the space to be thoroughly aware in the midst of the clamor of the world around us. How not to harm. Lately, I have been focusing on that subtle duct that allows us to change our perspective moment to moment from the subjective “what I am doing right now is of utmost importance and use to the world” to the interrelational “my actions are part of the ongoing flow of the world.” The latter implies that it is not “I” alone that am acting, but “I” am acting along with the world. Dogen put it so well when he said in the Genjo Koan,

To carry the self forward and realize the 10,000 dharmas is delusion.

That the ten thousand dharmas advance and realize the self is enlightenment.

To always try to keep that subtle distinction in our heart-minds as we breathe through the day of emails, cell phones, subway rides, horns honking, family and relationship demands—that would be of great value.

There seems to be such misinformation, even caricature, of Zen in the popular mind. Is there any simple way of articulating Zen to a general public?

Well, I’m not a purist. My heart teacher, Maezumi Roshi, would smile and say, “Fish can’t live in too pure water.” As I mentioned before, my own entry into practice came through the arts, compelling me to see that any entry, even a product ad for “zen furniture,” can be of use if it brings someone to practice. If it does not, well, so what, what is harmed? After all, “Delusions are inexhaustible.”

As for a simple way to articulate Zen? Most of the Zen literature is about just that, about finding expedient means to break through the dreams and screens of our minds. We build up an idea of what Zen is, and we thereby separate from it, creating a “Zen” that is outside of our own minds, of our own experience. How do I convey the incredible truth resident in the dharma without reifying it, without turning it into an idea that is separate from my life right now?

Each day, each moment, there arises an opportunity to express it, by actualizing my insight, or to kill it by turning it into an idea, a dream. One way, traditionally, has been to resort to direct, live interaction, to focus on its living-in-this-moment truth that is always right here and always changing. Thus, all the shouts and laughter. Right now, I suggest that Zen is being completely, thoroughly yourself, it is meeting yourself, and meeting what you may think is outside yourself, illapsing into that space where these two merge together. By the way, I love the word illapse. It means to slip in, to gently permeate. I think it gives the sense of the subtlety of the process.

How to articulate Zen? Each moment there arises an opportunity to express it…or to kill it.

You have led a few study retreats at BCBS using the texts of Dogen. Is this a Zen thinker of particular interest to you or your tradition?

When I read Dogen, I find it hard to believe that he wrote in the years 1230-1250, in an early Japanese syllabary. He seems so contemporary. He uses words to express a truth about the dharma, then to extrapolate, then to bend the meaning, then again to turn it upside down, to finally exhaust and renew it! Dogen never seems to let us hold on to anything. He is constantly deconstructing our notions, in the service of having us face the overwhelming subtlety and depth of the dharma. I find this exciting and I always learn something new when I engage Dogen. He is amazing. We are fortunate to have some wonderful translators who offer his teachings to us. He is also the called the founder of Japanese Soto Zen, though I doubt he thought of such a thing.

You are part of a pivotal generation in the process of transmission of Zen from east to west. Would you say that we are “getting it?”

Well, the way “it” is expressed continually changes. Yet, there is a continuity. So often we talk about the spatial transmission as in “from East to West,” but actually we also need to look at the temporal aspect, at how Zen has changed through time in every country. There are huge differences between 9th century Zen and 21st century Zen! What came to us here is really 19th-20th century Zen from 19th-20th century China, Japan and Korea.

So already, because of colonialism, capitalism, and all the “isms” of the past two centuries, that Zen that was transmitted was definitely different from Bodhidharma’s or the Sixth Patriarch’s.

In ancient China, they used the image of the veins in a polished gem to express the principle that continues, no matter how the gem is fashioned. I look at my transmission teacher, Roshi Bernie Glassman, as an example of the genuine dharma expressed as social action and spontaneous expression. Thus, right now, I see the Zen that is being transmitted here as authentic and true, and just as wild and interesting as in the old days.

Bonus Question: Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?

HA! Geographics! Look at the globe!