Based on an exploration of the principle of dependent arising in the previous issue of the Insight Journal, the present article proceeds to take a closer look at an aspect of one of its links: the five mental factors that make up “name” in name-and-form.

Based on an exploration of the principle of dependent arising in the previous issue of the Insight Journal, the present article proceeds to take a closer look at an aspect of one of its links: the five mental factors that make up “name” in name-and-form.

Name in Dependent Arising

“Name-and-form” as a link in dependent arising combines “form,” as the experience of matter by way of the four elements, with “name.” The implications of this term can best be appreciated with the help of a definition offered in the Sammādiṭṭhi-sutta (MN 9). This proceeds as follows:

Friend, feeling tone, perception, volition, contact, and attention, these are called ‘name.’

The definition of name proposed here does not include consciousness. Such exclusion is indeed required in the context of dependent arising, where in the standard exposition consciousness provides the condition for name-and-form. If, in this context, name were to stand for all that is mental and thereby include consciousness, it would imply that in some way consciousness is self-conditioning. For this reason, consciousness needs to be a link separate from name-and-form.

Role of the Five Factors

The five factors of name listed in the Sammādiṭṭhi-sutta are the mental activities required for the formation of a concept, for quite literally giving something a name. Bhikkhu K. Ñāṇananda (2003: 5) offers the following illustration:

Suppose there is a little child, a toddler, who is still unable to speak or understand language. Someone gives him a rubber ball and the child has seen it for the first time. If the child is told that it is a rubber ball, he might not understand it. How does he get to know that object? He smells it, feels it, and tries to eat it, and finally rolls it on the floor. At last he understands that it is a plaything. Now the child has recognised the rubber ball not by the name that the world has given it, but by those factors included under ‘name’ in nāma-rūpa, namely feeling, perception, intention, contact and attention.

This shows that the definition of nāma in nāma-rūpa takes us back to the most fundamental notion of ‘name,’ to something like its prototype. The world gives a name to an object for purposes of easy communication. When it gets the sanction of others, it becomes a convention.

The circumstance that there are five aspects of name can fruitfully be related to the etymology of the Pāli term for “conceptual proliferation,” papañca. Bhikkhunī Dhammadinnā (2017: 153n9) explains:

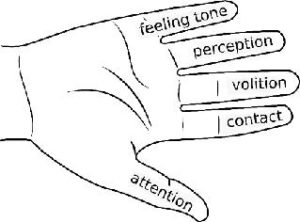

The etymology of papañca/prapañca is connected to the five-fingered hand and the numeral ‘five,’ with the preposition pra– (Pali pa-; Sanskrit pra-) plus the base for the numeral ‘five,’ pañca, which in Proto-Indoeuropean might have originally referred to the hand clenched to form a fist (the five fingers emerge, as it were, from the fist, from which they spread out) …

From a philosophical perspective, the etymology of pa-pañca seems to me suggestive of the fact that, from an early Buddhist perspective, even a so-called ‘first-hand knowledge’ (a metaphoric expression in several languages), is merely the ‘hand’ of pa-pañca and it remains ‘in the hands of’ pa-pañca to the extent that it is not emancipated from the notion of an ego, the sense of ‘I am’ being the basic import of papañca (asmīti … papañcitam, ‘”I am” is papañca,’ SN 35.207).

In other words, when the five (pañca) members of name get quite literally ‘out of hand,’ the result is conceptual proliferation (papañca). Expanding an illustration originally suggested by Bhikkhu K. Ñāṇananda (2015: 17), the five aspects of name can be related to the five fingers of a hand:

The Little Finger

The significance of each of the five aspects of name can be illustrated in relation to the five fingers of the hand.

The little finger, corresponding to feeling tone (vedanā), is easily overlooked. Yet, no hand is complete without the little finger. The influence of feeling tone on determining our attitudes and reactions is as easily overlooked as the little finger.

Yet, it is fundamental, comparable to hitting the table with the fist, when the little finger will be the first to make contact. Feeling tone is prominent at the first moment of contact and its hedonic quality tends to impact and reverberate through whatever happens subsequently. Much of apparently reasonable thought can turn out to be just a rationalization of the initial input provided by feeling tone in terms of liking and disliking.

Of further interest in exploring the role of this finger is also a gesture called “pinky promise” or “pinky swear” (“pinky” being a way of referring to the little finger). This takes the form of two persons entwining their little fingers when making a promise. The little finger is also the place where a signet ring is worn.

Feeling tone gets us hooked to experience similar to the hooking of little fingers in the “pinky promise.” Its promise is to provide lasting satisfaction, which it always fails to truly provide. In the end, feeling tone functions comparable to a signet as it seals the deal of experience through its hedonic quality: pleasant as a positive seal and painful as a negative seal, stamped on experience.

With all this far-reaching impact, on closer inspection feeling tone turns out to be as ephemeral as bubbles on the surface of water during rain (SN 22.95). It is, after all, just a “little” finger.

The Ring Finger

The ring finger receives its name for its traditional association with wedding rings. The role of perception (saññā) is indeed one that can be related to marriage. This type of marriage, however, is not based on a conscious decision to become engaged. Much rather, it is part of a construction of experience that is usually not noticed.

In agreement with cognitive psychology, early Buddhism considers experience to be constructed by the mind. This does not amount to an idealist position but only points out the impact of expectations and biases on what is experienced.

According to cognitive psychology, the tendency to construct experience is a by-product of evolution. Take the example of a Neandertal faced with a threatening situation, who had to make a quick decision on how to react. The faster the decision was made, the higher the chances of survival. Hence, waiting until all sense data had become fully available could turn out to be fatal. Instead, the mind learned to complete the picture by guessing what the first bits of information gathered must signify. Lisa Feldman Barret (2017: 83 and 86) explains:

you construct the environment in which you live. You might think about your environment as existing in the outside world, separate from yourself, but that’s a myth … your perceptions are so vivid and immediate that they compel you to believe that you experience the world as it is, when you actually experience a world of your own construction.

In this world of our own construction, perception furnishes the details for the construction work. It does so by “marrying” the information that has become available through the sense with whatever seems relevant in the mind’s store of memories. This performs an important role in making sense of experience, and even fully awakened ones will still have perception operating. But in the case of human beings who are not yet fully awakened, the operation of perception only too easily brings in prejudices and biases, experienced as aspects of outer reality rather than subjective projections.

In this way, perception is indeed the place of marriage between the subjective and the apparently objective, an understanding of which provides a key to insight into the mirage-like nature of experience (SN 22.95).

The Middle Finger

The middle finger is the longest of the five fingers of a hand. It has a central function in finger snapping, together with the thumb.

The length of the middle finger can be related to volition (cetanā), which is the mental factor that indeed seems to stick out and have the most long-ranging repercussions. From an early Buddhist perspective, volition is central to karma, as expressed in the following statement (AN 6.63):

Monastics, I call volition karma. Having intended, one does karma by way of body, speech, and mind.

The basic position taken here finds expression in a complementary manner elsewhere in the discourses. The relationship of volition to karma receives an additional highlight in an injunction in a discourse in the Nidāna-saṃyutta, according to which the body should be regarded as the result of former karma, constructed by volition (SN 12.37). A discourse in the Saḷāyatana-saṃyutta applies the same to the six sense spheres (SN 35.145), which should similarly be seen as the product of karma and volition.

According to a discourse in the Khandha-saṃyutta, volitions in relation to the objects of the six senses are what make up the fourth aggregate of saṅkhāras (SN 22.56).

The Samaṇamaṇḍikā-sutta (MN 78), which employs the term saṅkappa to refer to “volition,” shows that intentions of a wholesome or unwholesome type originated from a corresponding perception (the ring finger), just as wholesome and unwholesome deeds of body and speech originate from a corresponding state of mind.

In the ancient Indian setting, an emphasis on the crucial role of volition in relation to performing karma appears to have been a distinct position taken by the Buddha. For example, the Upāli-sutta (MN 56) shows the Buddha debating this position with Jains, who asserted that, from the viewpoint of karma, bodily deeds are more important than mental ones. Although this might at first sight seem a persuasive position, the Buddha countered by clarifying that, inasmuch as bodily deeds depend on intention, the latter is rather the crucial factor for karma.

The same principle can also be seen in monastic law as described in the Vinaya, where often the intention behind a particular deed can determine if a breach of the rules has taken place. For example, if something was taken out of a wish to steal, the perpetrator has committed a rather serious breach of monastic conduct and thereby lost membership in the community of fully ordained ones. Without such an intention, however, the same act does not have such repercussions (Vin III 62).

All of this converges on the central importance of the middle finger of volition. In conjunction with the thumb of attention it can act like a finger snap, by way of calling attention to what is happening.

The Index Finger

The index finger or forefinger serves to point things out. This gesture tends to be done by babies as young as one year. Thus, the index finger is involved in a very early form of communication in the development of a human being.

Contact (phassa) in a wayserves to point things out. Just as when we want to do any work, we need to find a place for doing it, so contact is the place for experience to occur, where the conjunction of sense organ and sense object can take place. In other words, contact provides the site for experience.

The index finger is also quite dexterous compared to the other fingers already mentioned. At the construction site of contact, a similar adroitness can be witnessed, which involves a constructor and the construction material. These are respectively name and form.

The Mahānidāna-sutta (DN 15) explains that the resulting construction involves two types or dimensions of contact: resistance (paṭigha) and designation (adhivacana). Form is “contacted” through resistance, just as name is “contacted” through designation.

In the case of formless meditative attainments (such as boundless space, boundless consciousness, etc.), the constructor has in a way run out of material supplies and keeps reworking what is already there. No more resistance is involved, only designation contact produced by the single constructor of name.

With the experience of Nirvana, even the constructor has been left behind. Since the construction site only exists as long as some construction is being done, at this point the site is also left behind. When cessation is “contacted,” nirodham phusati, contact ceases, phassanirodha. This in turn serves as the ultimate confirmation of the insubstantial nature of experience and the fact that even contact itself, as the site for construction, is constructed.

The Thumb

The thumb is the finger that clinches the deal. Putting up the thumb signifies approval, just as putting it down conveys the opposite. The thumb is the finger most needed in order to take hold of things.

The role of attention (manasikāra) is indeed to take hold of things, by way of determining which aspect of experience is being attended to. In this function, attention can also be considered as particularly versatile among the factors of name, just as the thumb is the most flexible of all five fingers in terms of movement.

By singling out what is of interest, attention functions to some extent comparable to the expression of an evaluation by way of thumbs-up and thumbs-down. This could be taken to illustrate the two-fold nature of attention, which can be either wise or penetrative (yoniso) or its opposite of being unwise or superficial (ayoniso). Whereas the former leads to liberation, the latter leads to bondage. Hence, the crucial question with attention is how it is being deployed:

![]() wise/penetrative

wise/penetrative

![]() unwise/superficial

unwise/superficial

Both types of deployment of attention involve the other fingers of the hand. All five fingers are required for a fully functional hand.

In the same way, all of the five factors of name are required for fully functional mental operations. They indeed remain operative even in an arahant. The crucial difference is only that the five fingers of an arahant no longer get out of hand; they no longer produce conceptual proliferation (papañca).

A pdf version can be downloaded here.