Rosalyn Driscoll is a visual artist whose sculpture, installation, collage and photography is sourced in the body and sensory perception. She animates her sculptural works through video, dance and theater, and collaborates with scientists. She is a member of Sensory Sites, an international art collective, and her work has been exhibited in the US, Europe and Asia and awarded numerous fellowships. Her book, The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts (Bloomsbury, 2020) explores the grounds for integrating the bodily, somatic senses in our understanding of how we make and engage with visual art. She has been instrumental in the development of the Dharma and Arts program at BCBS. A pdf version of this article can be downloaded here.

Rosalyn Driscoll is a visual artist whose sculpture, installation, collage and photography is sourced in the body and sensory perception. She animates her sculptural works through video, dance and theater, and collaborates with scientists. She is a member of Sensory Sites, an international art collective, and her work has been exhibited in the US, Europe and Asia and awarded numerous fellowships. Her book, The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts (Bloomsbury, 2020) explores the grounds for integrating the bodily, somatic senses in our understanding of how we make and engage with visual art. She has been instrumental in the development of the Dharma and Arts program at BCBS. A pdf version of this article can be downloaded here.

I’m a visual artist in the sculptural tradition and a Buddhist practitioner in the Theravāda tradition. I took up the practice of these two traditions at roughly the same time, fifty years ago, in my early twenties. Since then the relations between these practices in my own life have been complex and dynamic. While Dharma and art inform and illumine each other in myriad ways (and for some people, there’s no distinction), I want to focus on a fundamental aspect of both practices that seems kindred in spirit. I’ve begun to think of the aesthetic experience—whether one is perceiving a work of art or making it—in terms of my understanding of mindfulness. Mindfulness offers a new way to understand the aesthetic experience. It generates insight into the meaning and purpose of art.

Aesthetic experience often mystifies me. Why do I come away from a harrowing art exhibition, movie, or play feeling curiously uplifted? Why do I feel magnified upon seeing Picasso’s Guernica, from which I can almost hear the shrieks and groans of its war-torn figures? Or Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, with its encyclopedia of suffering? And Shakespeare’s Hamlet, that ends with everybody we care about dead? What do these great works of art do to my consciousness?

Let’s begin at the other end of the spectrum, with brief, spontaneous aesthetic experiences. On many occasions throughout the day, I notice a slight shift from ordinary, functional awareness to attend, however fleetingly, to sensory, perceptual dimensions of the world around me. I notice the slant of light through trees, the smooth heft of a ripe eggplant. I notice the soft edges of my dining table, the worn grain, warm hues. The utilitarian perception of my table as a surface on which to place food yields to a very different perception, and a very different relationship. This tiny shift in attention pulls me out of my thoughts about putting dinner on the table. I leave my self- and goal-oriented stance and take in the available integrity and beauty. This small attentional shift always makes me feel refreshed—appreciative of the world around me and enlarged by the capacity to perceive in this sensory, aesthetic way. (“Aesthetic” is derived from the Greek word for perception by the senses).

A similar dynamic takes place when I approach an artwork, though on another scale and with different intentions. Engaging with an artwork is an expanded version of the small daily shifts in attention from instrumental to aesthetic. As I enter the world of an artwork, I undergo a change in my attitude and awareness. I open into other realities than the one I’m accustomed to. The world an artwork reveals to me may relate to everyday reality, but is also, at the same time, different than ordinary reality. I recognize the artistically transformed world is an invention, a creation, a fiction—whether a painting, play, dance, poem, novel, song, or photograph. An artwork is a fabrication that derives from and participates in, but is not bound by, conventional reality. Artworks emerge from life, reflect life, and inform life, but possess a different formal, emotional, psychological, ontological status by virtue of their focus, intensity, and transformation of what we consider ordinary.

We willingly believe in the world that is revealed in the painting, movie, or music, and at the same time we know it lives beyond or outside or inside or underneath daily reality. Enthralled by a play in a darkened theater, my pragmatic, habitual consciousness yields to aesthetic, imaginative consciousness. The usual perceptions fall away. Or, as many have said, we willingly suspend disbelief. We have the capacity to believe and at the same time to know it’s not “real.” This knowing awareness creates a larger place for us to inhabit. We have the ability to sink into the narrative or content of an artwork while remaining aware of our responses (whether aesthetic, perceptual, sensory, emotional, psychological or somatic). This capacity for reflective awareness is a gift of consciousness.

Such reflective awareness comes to another kind of fruition in Dharma practice. Mindfulness allows us to reflect on our experience—to know that we know and to know how we know. We can be absorbed in a perception, and we can reflect mindfully on the perception. This degree of reflection or mindfulness creates space, however small, around the object of our attention. We take a step away from it, allowing ourselves to perceive it without being entangled or identified. This subtle shift generates a more spacious, generous mind-state, fluid and capacious enough to hold seemingly disparate points of view. We can choose to regard or embrace the perception. We can summon a different attitude toward it, such as kindness, clarity or equanimity, rather than succumbing to its habitual demands. We build the capacity to refrain from automatically moving through craving, clinging, perceiving and becoming in the chain of dependent origination. Not bound by identification nor adrift in dissociation, we are free to move nimbly and lightly between immersion and reflection.

A similar mindful, creative awareness functions in the aesthetic experience of an artwork. We are able—even invited—to play in the fields of perception, attitude and belief. This creative awareness is fundamental to the power of art. The experience and cultivation of the capacity for reflection—to know that we know—may be the deepest purpose of art. It may be the most profound, perennial effect art has on our wellbeing. Underneath art’s perceptual feats, revolutionary ideas, compelling stories, communal bonding, startling representations, power of communication, capacity to provoke wonder, and stunning beauty lies the invitation to experience reflective, mindful awareness. Making and experiencing art provide training grounds for the native ability to reflect on and transcend our limited situations and the usual contents of our body-minds.

When I create a sculpture, I call on my intelligence, skill, body and heart to transform the materials (and my consciousness) into a new reality, a world with its own rules, boundaries, language and structure. At the same time, from a different perspective, I know what I’m making remains a fabrication of steel, rawhide and rope. I can explore both kinds of relations at the same time or in dynamic oscillation: I can immerse myself in making an artwork and I can pause to reflect, to pay a different kind of attention. The oscillation between immersion and reflection is built into the creative process. I focus on shaping a piece of metal, choosing a color or tying a rope, and then I step back, perhaps literally but certainly imaginatively, to reflect. I open the space for contemplation; sense what’s at play; grasp and understand what I have done; ask what interests me; calibrate how well it accords with my purposes; consider the possibilities open at that moment; and sense what the next move might be. This hiatus for reflection is crucial for assessing whether or how the work aligns with my questions, concerns, and desires. In asking myself, “Does this weight, this curve, this material, this direction feel right?” I am searching for clues for how the work-in-progress furthers my investigation. I inquire whether it reveals new information about the question I’m asking; whether it evokes the precise feeling I pursue; if it opens new avenues of exploration; or if it resolves my uncertainty. Such assessment is essential to the creative process. The ability to move between the two poles of immersion and reflection is a skill I can learn, practice, and refine: when to step back, when to dive in, how far or how long to step back, how far or long to dive in. The stepping back can last for milliseconds or years. It can be intentional or unconscious. It can vary in intensity and degree.

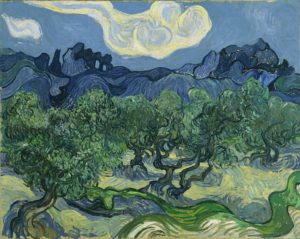

The aesthetic experience of an artwork by someone other than the artist resembles the process the artist uses. As a perceiver, I allow an artwork to capture me with a story or image, but I am also able to shift my attention to the art and craft of its making—to the medium, method, or process by which it was made. I move from emotional appreciation of the content of an image to aesthetic, sensory appreciation of the process of its making. This dimension is crucial to the effect an artwork has on us. A story may be told in many ways, but the way it’s told will determine its efficacy and power. A painting by Van Gogh portrays an ordinary row of trees along a road; but the brushstrokes—short, vivid and energetic, arrayed in patterns and rhythms—imbue us with a feeling of vitality. Hamlet’s soliloquy speaks of suicidal doubt but his language makes the heart sing. We can discern the difference between content and process, object and medium, reality and illusion. We take pleasure in being able to hold these two aspects simultaneously, or to go back and forth. This holding of both/and creates a third space to occupy. It generates a sense of agency and freedom.

Artworks enable us to grapple with suffering, discontent, groundlessness, chaos, dread, despair, or violence, not as raw reality but as mediated and transformed by their passage through materials and processes, through the struggle to contain them in a vessel of human making, and through the crucible of the specific, personal life of the maker. A space emerges from that process, a crucial distancing. We can create intimacy and distance at will. In a painting of a crucified saint by Francisco de Zurburan, Saint Serapion, the upper body, outstretched arms and bent head of the saint face me, filling the frame and generating a feeling of intimacy with his suffering. But the main character in this quiet, restrained drama is the saint’s beautiful, cream-colored robes. Their deep folds, shadows, and warm highlights ground the saint’s death in sensuous, felt reality and formal beauty, lifting it into apotheosis.

The clay in Alberto Giacometti’s figures has been relentlessly gouged, pinched, and removed, making the gaunt, bronze bodies feel ravaged, but reduced to an essential, adamantine core. Goya’s series of prints, Disasters of War, show people killed and dismembered, but his mastery of ink, mark, and paper, his striking compositions, and his trenchant lines mediate the horror. I gain distance from the unspeakable at the same time as I confront it.

I am able to modulate my engagement with the pain I feel. I participate fully in the subject and yet remain aware of the artwork as a creative interpretation. I recognize it is not the tragedy itself but a reflection on the tragedy. Italo Calvino writes of this necessary reflection in Six Memos for the Next Millennium when he describes how the Greek hero Perseus managed to cut off the head of the Medusa—whose face turned into stone whoever gazed upon her—by watching her reflection in his bronze shield. Furthermore, Perseus carries the bloody, severed head with him, hidden in a sack, to pull out as a last defense when in danger of defeat, turning his enemies into statues.

Perseus masters that terrible face by keeping it hidden, just as he had earlier defeated it by looking at its reflection. In each case, his power derives from refusing to look directly while not denying the reality of the world of monsters in which he must live, a reality he carries with him and bears as his personal burden.

When I encounter artworks that reveal the magnitude and depths of human splendor and depravity, I acknowledge the full range of the human condition and of my own possibilities. I feel broader and deeper. I am more cognizant of who I am, who I am not, and who I might be. I leave my habits and personal concerns behind. I move from a narrow sense of self to a larger scale of being. The artist’s willingness to grapple with such demanding realities inspires my capacity to do so. I see suffering and feel it more fully. The artist’s ability to transform life’s challenges into compelling imagery enables me to perceive freshly and in a different way. This reinvention of perception and reality is not just refreshing. Re-creation becomes critical for meeting new individual and collective challenges. As we find ourselves facing historically unprecedented conditions, we need artists to invent new languages, perspectives, and tools for transformation. I think of Anselm Keifer’s huge paintings of the post-Holocaust landscape, in which blasted, desolate plowed fields contain seeds of fertility in their deep, gouged, sculptural furrows.

Artworks also offer us experiences of coherence, order, magnitude, peace, and transcendence. We empathically, somatically tune ourselves to clarity and spaciousness, discovering these qualities within ourselves. Janet Echelman’s ethereal, colored nets, such as As If It Were Already Here, float hundreds of feet above the viewer, revealing the flow of wind, light and weather within a cosmic vision.

As an artist I engage with materials and forms in the physical world in order to render my perceptions and emotions more visible and palpable to myself and to others, and to move beyond habits and conventions. In this transformation, the artwork creates a middle ground between the world and my response to the world. By infusing canvas, sounds, the body, or words with my inner life, I create a new entity. In the words of the great South African artist, William Kentridge, “we meet the world halfway.” This new entity (the artwork) lies in “the mediated space between ‘it is’ and ‘it seems to me’.” It creates territory between physical matter and mental phenomena, partaking of both. It stands between myself and other people, offering a rich, complex place where we might meet. It offers a middle ground where people of different cultures and ideologies may gather.

Like the flexibility developed in Dharma practice, opening to artworks teaches us to move nimbly between perceptual frames. To step outside a limited, narrow, inherited, or prescribed sense of self. To question reactions and assumptions. To slip inside another’s skin. To rewrite and recreate history. To engage with appetites, gods, and forces beyond our control. To envision new, unimagined possibilities. To shift perceptions, drop beliefs, and change identities. To empathize, resonate, and relate. To learn larger, more compassionate, responsive ways of being.

In Dharma practice we cultivate anatta, unwinding the enchantment with the sense of self as we habitually enact it. The kind of aesthetic experience described here gives us a taste of non-clinging to self. Art proffers an invitation to move beyond our usual experience of ourselves. This move may diminish—however briefly or deeply—protective, limiting self-absorption. At the same time, the aesthetic experience enhances and speaks to our particular body-mind, senses, emotions, and psyche, and to our unique sensibility and search for meaning.

The capacity to embrace multiple ways of being and doing enables us to move more fluidly through the difficulties and joys of life, to deeply engage with them yet not be defined, bound, or limited by them. We open to the plenitude and mystery of the moment.

This article is based on material from The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts by Rosalyn Driscoll, Bloomsbury, 2020.