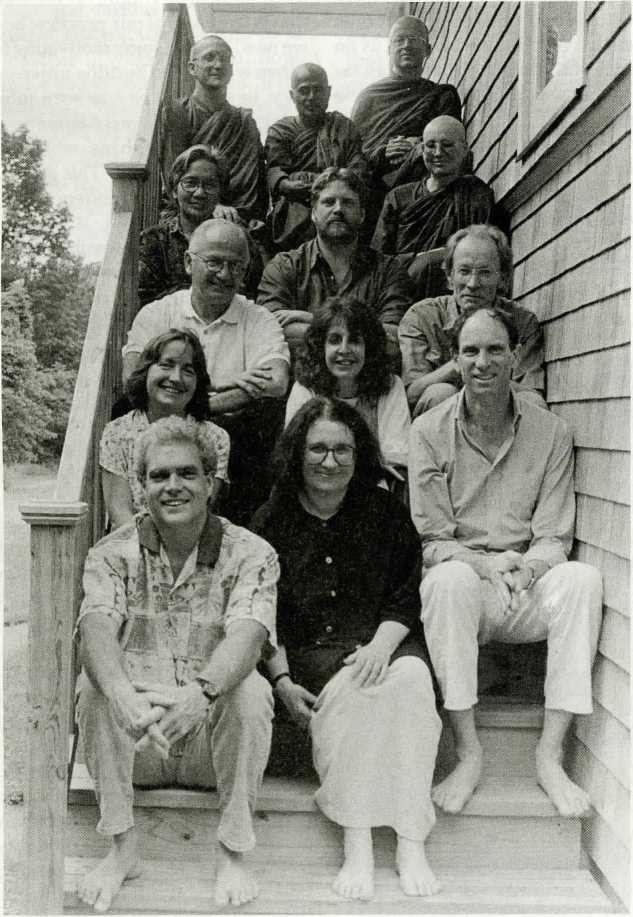

The multifaceted challenges of contemporary Buddhism were explored during an historic weekend conference—to our knowledge, the first of its kind—held last June at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Twelve leading teachers of Theravada Buddhism, equally representing the lay and monastic traditions, addressed cutting-edge issues arising from the relatively recent introduction of Theravada Buddhism to the West.

Throughout its long history, Theravada Buddhism has existed in a protected environment in southeast Asia. Today, both lay and monastic practitioners are finding that Western culture, especially in America, is less than protective of the norms and forms that have prevailed for so long in Asia. As a result, many western teachers of vipassana meditation, trained in Asia in the seventies, feel a greater need than ever before to preserve the essential aspects of their Theravada heritage in the West.

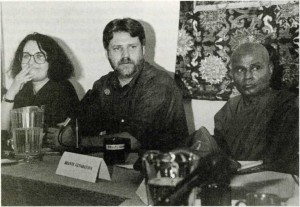

Encapsulating the spirit of the larger inter-Theravada dialogue in his opening remarks, Andrew Olendzki, conference moderator, encouraged the panelists and about 75 audience members to “open up to a diversity of views and opinions.” He urged them to,” to speak frankly, to speak up, and speak often.” “I feel confident,” he continued, ” that whatever issues we get into can be held in the context of mutual respect and understanding. And I think within that context there is room for a great diversity of opinions which we hope to encourage, if not actually provoke!”

Five panel discussions sought to address a number of issues germane the inter-Theravada dialogue. Each discussion panel had an overarching theme and a subset of specific questions intended to elicit in-depth response from the presenters as well as the audience. What follows is a brief sampling of those responses.

First Panel Discussion: What is the meaning of the Buddha’s Awakening? What did the Buddha awaken to? What does his awakening mean to you?

Thanissaro Bhikkhu: There are two aspects of the Buddha’s awakening that are really important for us: one is the What, and the other is the How—How he came to an awakening, and What he awakened to. It is crucial for us to understand that in the Buddha’s awakening these two aspects come together; you can’t have the What without the How, or the How without the What. The What is the fact that there is an unconditioned, that there is a deathless element; and it is the highest form of happiness; and it can be attained through human effort. The human effort involved is the How. You can’t attain the Unconditioned in any true form until you have taken the conditioned apart.

Without knowledge of the conditioned, or how the conditioned reality basically functions and how it runs, and without an understanding of karma and the role that karma plays in this, no realization of boundlessness or emptiness can really count as an awakening. This is because the How is as important as the What. Without the How, without the ability to take the conditioned apart, there is no real breakthrough to the Unconditioned. True awakening of necessity involves both ethics and insight into causality.

Christina Feldman: As I looked at the different presentations of the Buddha’s awakening (during my first encounter with Buddhism), it struck me that there were basically two versions of liberation: one version regarded awakening as an experience you had in meditation, an experience that was probably going to be temporary.

Christina Feldman: As I looked at the different presentations of the Buddha’s awakening (during my first encounter with Buddhism), it struck me that there were basically two versions of liberation: one version regarded awakening as an experience you had in meditation, an experience that was probably going to be temporary.

The other version of liberation was that it was not about an experience at all, that it was about understanding. It was about the liberating insight that revealed the transparency of the world of appearances. In this version, it was awakening to an understanding of an Unconditioned, a timeless reality. And through that insight the veil of ignorance was dissolved.

Personally, I incline towards awakening as not being a temporary fleeting experience or a glimpse of a moment, but as a very liberating understanding. I don’t actually feel that ignorance can ever be chipped away at through experiences. But I believe that ignorance is dissolved through an understanding of the nature of the Unconditioned.

Ajahn Passano: I think one of the qualities which is most helpful is the arising of faith. The actual basis for faith in the Buddha’s teachings is in the enlightenment of the Buddha. The essential quality of faith, of devotion, of confidence—that is the basis of our practice, because we need to have some motivating factor. When we come to Buddha’s own experience, he says that he was bom subject to aging, death, defilement as we are. But he was able, through his own efforts, to realize enlightenment. This gives us the example and the confidence that it is possible for us as well. It also gives us confidence in what is possible as the highest potential for a human being. This faith in the enlightenment of the Buddha is really a faith in our inherent wisdom; it is the beginning of the path. It is also essential for recognizing the path. Faith leads to effort.

There can be so much time and energy focused on speculative inquiry. That’s why I think it’s important to establish faith, so that we can practice.

Dr. Thynn Thynn: In 1972, when I was 30 years old, I went to the Mahasi Center (in Rangoon) and sat a few sessions of meditation. Well, nothing much happened during the session, but to my great surprise, after those few sessions, I found myself very free. I was more free from emotions, free from turmoil. I thought to myself it is from those meditation sessions, and I was very delighted…. My subsequent teachers were teaching mindfulness in everyday life—that if you are aware of, mindful of your thoughts and feelings they will fall away and you’ll find peace, you’ll find freedom. So, I thought to myself, “Oh, that’s for me.” I studied with them for about eight months, and I cannot explain the kind of opening up that occurred in my mind. It was at that point that I really appreciated the Buddha’s awakening, what the result of awakening is; and his great compassion that led him to teach for so many years. I felt extremely appreciative that this teaching was able to touch an ordinary person like me, a speck in the dust somewhere. To be able to enjoy the fruits of his labors was something very profound.

Second Panel Discussion: What does Theravada Buddhism have to offer the West? What is unique about it? How does it relate to what is already here?

Sister Candasiri: There is the encouragement mentioned in the Kalamasutta, not to rely on what one has heard, or on tradition and various other things, but to actually test out these teachings and see whether it works for you, how it works for you in your own lives. If I live carefully, responsibly in the society, what is the result? Do I feel happy? Do I feel a sense of self-respect? Am I at ease in myself and the society? And with the people I have to live with? And then the opposite. If I act and speak in unskillful ways, what is the result of that? So, right from the start the Buddha was encouraging a very serious and responsible investigation into what he was presenting. It wasn’t just that you have to believe that this is how it is, this is the truth, and you’ve got to live according to this. This is something that I feel is quite significant about the presentation of what has come across in this [Theravada] tradition.

We are very fortunate that the Vinaya, the Patimokkha, the How (if you like) one makes the teaching come alive in one’s life, has been preserved. This is a social structure. It covers every aspect of life. One of the things that delighted me most about this tradition when I first came across it was its all-inclusiveness. And this seems to be a very beautiful model. For us one of the greatest challenges is to consider if it is something that’s relevant. And how would it work? Perhaps we can note that it is in fact working in England where we have four monasteries.

Vimalo Kulbarz: What I have found unique about the teaching of the Buddha is its enormous comprehensiveness. It’s a very wide teaching, impressing all aspects of our life. I personally feel that there should be an openness with regard to other traditions. Due to a certain historical situation, Theravada Buddhism came to countries in which there was not a highly developed religion. The situation in India or China was very different. If there is no challenge, anything can be preserved. They sort of repeat the words; it’s very easy. And one can make a virtue out of it. But there’s also the danger of stagnation; and the Theravada tradition is only really being challenged now.

Out of our investigation into what is the real essence, we find the form that is most suitable here in the West. It is not that either form is good or bad; it is a question of whether we know what we are doing. If there is a real sincerity and a real understanding of what it is to bring over and preserve in a certain form, that can be very good. There is also the great danger of just keeping the form, which can be an empty husk. In the spiritual life there are dangers and traps everywhere.

Christina Feldman: One thing which I think is a gift of this tradition is its accessibility, its availability. You don’t have to sign any kind of code of allegiance to join up; you don’t have to wear a uniform; you don’t have to adopt a belief system; you don’t have to learn a new language; you can just learn about the heart of this tradition. To me, this is a remarkable gift in a world which is so filled with opinions….Unfortunately, a lot of people think that meditation is the whole story. I think it’s important for us to have a complete picture which includes study, which includes practice, which includes ethics, which includes community. But we are in the very early stages of this tradition in the West. We have time, actually, to bring all this together.

Steven Smith: I think in this discussion of the Dhamma moving to the West, we need to evoke our own images, our own myths. Many of the ancient traditions have such universal messages that they very smoothly transplant over here. They’re embedded with very powerful, mind-awakening symbols that activate an inner climate of possibility—possibility for insight, for transformation. The symbols of these stories are quite universal, quite timeless. To enter these stories is to enter a mythic, non-ordinary space/ time dimension, which sometimes allows for very direct understanding.

Steven Smith: I think in this discussion of the Dhamma moving to the West, we need to evoke our own images, our own myths. Many of the ancient traditions have such universal messages that they very smoothly transplant over here. They’re embedded with very powerful, mind-awakening symbols that activate an inner climate of possibility—possibility for insight, for transformation. The symbols of these stories are quite universal, quite timeless. To enter these stories is to enter a mythic, non-ordinary space/ time dimension, which sometimes allows for very direct understanding.

There is a wisdom or compassion that bypasses the rational mind, the intellectual mind, goes right to the heart in both telling the stories and hearing them….

But we still need our own stories and our own figures in them with whom we can identify. Some of the stories need to be stripped, I think, of their ponderous moralisms and sexist overtones. But nearly all of them reveal to me gems of wisdom and compassion.

Third Panel Discussion: Intepreting the Dhamma for the West: Some of the teachings in the Tipitika on the nature of mind and consciousness are subtle and profound and have resulted in various interpretations—in the different schools of Theravada, as well as in the later traditions. How are we to understand the teachings about pabhassara citta, the “radiant mind?”

Joseph Goldstein: One of the reasons I first began thinking about a conference like this was to address this very question. For me, the basic question boils down to the relationship between awareness and the Unconditioned, between awareness and Nibbana. The heart of the Buddha’s realization was the experience of what we call the Unconditioned. So, it’s at the very core of what our practice is all about.

And my experience has been that within the Theravada tradition there are two quite divergent views about what constitutes the nature or the experience of the Unconditioned. Hopefully, the discussion today will explore whether in fact these two views are quite different understandings of what constitutes enlightenment, or whether it’s simply a matter of different descriptions.

Both of these perspectives come out of great and profound practice lineages. They are coming out of people’s very deep realization, so this is not a philosophical discussion. This is really a discussion based on the deepest aspects of people’s spiritual practice and realization.

The first viewpoint, coming out of the Mahasi Sayadaw tradition (also the Visuddhimagga and the Abhidhamma tradition) is there is no state of awareness or consciousness outside the five aggregates. In this way of viewing things, the cessation of the aggregates is called the highest peace. In this viewpoint, Nibbana or the Unconditioned is the cessation of conditioned phenomena.

The other viewpoint is represented, in my understanding, by many lineages within the Thai forest tradition. In this perspective, suffering is understood as the aggregates being clung to. And in the absence of any clinging, awareness is free, it’s unconstructed, it’s unsupported.

Bhante Gunaratana: Our entire samsaric existence is explained in terms of the nature of consciousness and how it initiated our life which is a mass of suffering. Our happiness, our unhappiness, and everything else we do intentionally depends entirely on the nature of consciousness. Because of the complex nature of “consciousness,” semantic interpretation of the word is very difficult. As it involves everything that mind is, many synonyms with different shades of meanings have to be used. Buddha himself used the three Pali words mano, citta, and vinnana synonymously.

Mano comes from man, to think; citta comes from the root cit or cint, to think. And vinnana from vi and jna or vid and jna, to know. I would like to make a very brief and dhammic survey of these three words before attempting to treat the nature of consciousness in some detail.

Vimalo Kulbarz: I have the rather heretical notion that most of the central concepts of the Mahayana are in the Pali Canon. Many of them are not mentioned in the Theravada tradition. And this term that we are talking about here, pabhassaram citta—the originally luminous mind—is found again and again in the Mahayana sutras as Buddha-nature. Why is it totally ignored in the Theravada tradition?…. The reason, I think, is that many of these translations were done by scholars who only knew the language (Pali). Unfortunately, that doesn’t convey wisdom. And unless one has experienced these things the Buddha speaks about, through meditation or some mystical experience, they mean nothing. They are just words. So, I think that is where certain things are left out.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu: From my experience, there are basically two types of meditation teaching: one is the reprogramming type, where someone says, “You’re going to see that all things are not self, all things are impermanent, all things are suffering.” And the more completely you can reprogram your mind, you win. The problem with this, of course, is that you can convince yourself that you have really seen things as you’ve been told to see.

The alternative way is what I call the treasure hunt method, which I think is the way the Buddha actually taught meditation. He said that there is an Unconditioned. And if you look at things in terms of the fact that they are not-Self and just keep stripping away to see whatever does not pass the test of inconstancy, stress and not-self, eventually you’re going to find something in there that is unconditioned. And he doesn’t define it in greater detail, so that you don’t have too many preconceived notions about what you’re looking for.

A very useful test case, often taught in the Thai forest tradition, can be: once you get into a state like this (resembling the Unconditioned), can you take it apart? Can you see that there are causes operating in there? Can you see any slight bit of attachment? And if so, take it apart.

One forest teacher, Ajahn Maha Boowa says that when you get down to a state of mind which is radiant or shining and it seems to be the most precious, most valuable, most wonderful thing that could possibly happen, you take care of it because it does seem so precious. And you lose sight of the fact that you are taking care of it. And the only reason it stays is because you are protecting it so much.

One forest teacher, Ajahn Maha Boowa says that when you get down to a state of mind which is radiant or shining and it seems to be the most precious, most valuable, most wonderful thing that could possibly happen, you take care of it because it does seem so precious. And you lose sight of the fact that you are taking care of it. And the only reason it stays is because you are protecting it so much.

Fourth Panel Discussion: Who is a Dhamma teacher? How does a teacher of Theravada become a teacher? How important is the role of lineage and formal transmission? What do the teachers owe their students? etc.

Sharon Salzberg: What it means to be a teacher in the Theravada tradition is a very interesting question because the range of teaching needs in our country is enormous. There’s a huge, complex array of needs. It seems that wherever there’s suffering, there’s a call for the Dhamma, and that’s a lot of places…. There’s a very beautiful and natural way in which people seem to become teachers, arising out of the intentions, desires, and the respect of the community. In that model, the students empower the teacher. They sense that somebody has something to offer and they seek it out. They choose this person.

The question of motivation, of course, comes in again in terms of why we teach. Are we teaching out of a sense of compassion, out of a sense of the love of the Dharma? Are we teaching because it’s a nice life? Because there’s a certain degree of personal power in that? We need, I think, to continuously ask ourselves these questions.

One of the greatest strengths we have [here at IMS] in our understanding of our motivation is the fact that we often have a sense of team teaching. We also have a great amount of dialogue with each other. There’s a tremendous benefit for those people who are connected and in contact with each other, especially the teachers.

Bhante Gunaratana: Friends, this is a very important question. I think Theravada teachers, like any other teachers, should know the subject quite well and be able to return over and over again, like fish going to water, to the Dhamma texts as a reference point. There are not that many monastic teachers to go around [here in America] and the burden has been greatly relieved by very compassionate, very good lay teachers. And these teachers, I’m pretty sure, are going back, over and over again, to the texts. Not secondary, not tertiary materials, but the original texts, the source….

The question who decides who can be a teacher, that’s a tough question. Who decides? I think students decide who should be a teacher. There are some who try to teach with very good intention, but they cannot convey the message because their understanding, their relations with students are not very healthy. And therefore they lose students. When the teacher starts with fifty students and ends with two, then the students tell the teacher, “You are not a good teacher.”

On the other hand, since we don’t have teacher training colleges for Buddhist teachings in modem western society, it is not very easy to select good teachers. By the response of the students, though, there is eventually the process of elimination.

Michele McDonald-Smith:

I would hope that all of us in the hall would agree that sila [virtue, morality] is really important. I find that one of the things I love about this tradition is the foundation of sila, the emphasis on sila, in the beginning, in the middle, and the end of practice. And if one looks at the texts, I think that you can find some standards for teaching in terms of sila, samadhi [concentration], and panna [wisdom]. Teachers can be incredibly profound in terms of their ability to speak. They might have incredible clarity and yet somehow their wisdom is not embodied in action. I call that disembodied clarity. And one can see a lot of disembodied clarity around the planet.

One of the things I appreciate about the students in the West is that they are very practical. And they’re demanding that mindfulness apply not only to a monastic retreat situation, but also to how they relate to their kids, or how they relate to their partner, or driving in traffic, or any emotional difficulty. People don’t just want a model where somebody holds up a carrot and says, “This is where you can be,” a perfectionist model. People want a holistic model where it applies to their life.

I think one of the biggest challenges of being a teacher in the West is being able to have empathy with [the student]—and have understanding of the psychological level. And to be able to guide the person from the level where they are now to a deeper level in whatever time it takes. This means being able to follow that person in the way they need to go. But also to have the strength to take them to the depth when that can happen. That takes a certain kind of fine-tuning which is remarkable. It takes a lot to be able to have a fluency with all of the levels that people come in with, including the enormous self-hatred that seems to be so predominant in the West.

Larry Rosenberg: It’s probably a safe assumption that all of us western teachers have gone through a lot to bring the teachings here…. So, in some ways we’ve met a challenge. But I’d like to suggest that what awaits us now dwarfs this challenge—it is much more severe and much more subtle.

I have this image of the Dharma in the West as someone surfing and a huge tidal wave approaching. And the tidal wave is success. It’s pretty easy (even though it’s difficult) when you get the teachings you love from teachers whom you respect and then bring back these teachings. There’s a kind of heroic strengthening that comes out of that. But now it’s different.

The next challenge is already here. What I have seen is that in this country nothing fails like success. What seems to be happening is a tremendous receptivity towards what we’re doing. And, of course, that’s good. That’s part of why we’re all doing this. So we’ve done our job well in some sense. But also the need is just overwhelming.

I think the scale is now colossal with the mass media. That is, the amount of fame, money, sex, power that’s available almost overnight is staggering. So, for me, a teacher has to be able to stand up to that, to not be sucked into it. And, of course, all the things we have been talking about [in the conference] are different ways to make sure that that happens.

Closing Discussion: Imagine that we are meeting again 20 years from now to review the way the teaching and practice of the Dhamma has developed in the West in the intervening time. What changes would you hope to be able to point to as signs that the practice in the West has matured?

Michele McDonald-Smith: I thought it would be interesting if all of us came back twenty years from now and nothing had changed. Except that we looked different. I don’t really have a clue what’s going to happen. I think that it’s really interesting to see what will happen, but it’s out of our hands other than the little bit of contribution that we each make. It would be nice if a little more ignorance in the world was wiped away in myself and in others.

Christina Feldman: I could imagine us in twenty years sitting here shaking our walking sticks at each other and arguing over the meaning of the Buddha’s awakening! And, actually, I think this is a sign of good health. I hope in twenty years we haven’t come to any conclusions. Certainly in twenty years I would hope to see many liberated yogis. That’s a sign of maturity of the practice. I would hope to see that we have perhaps given more attention to the development of sangha and community.

Sharon Salzberg: I think those of us who are teachers and those of us who are students are really just living our lives in the best way that we can. Those of us involved in these organizations are guiding them or serving in them to the best of our ability. We’re all just doing what we do, and it will fall into place, or fall apart and then into place, as time goes on.

Joseph Goldstein: For me the heart of what I would like to see happen is really the development, the deepening, the great enlightenment of teachers and students. Somehow, that’s what it’s all about. That’s what the Buddha was teaching. He was teaching awakening. I think what it takes is a tremendous commitment to practice, even by a very few people. And so what I would love to see happen are practice opportunities for that to occur, where people really could just go for it and accomplish it and teach the rest of us.

Andrew Olendzki: America’s been so successful in establishing—enshrining, almost, as virtues—the qualities of greed, hatred, and delusion. Greed through consumerism and the pursuit of progress; hatred through racism and bigotry; delusion through advertising and various other mass-constructed illusions. I’d like to see some progress to reverse that. I think Buddhism has a tremendous contribution to make in putting into the mainstream culture the antidotes to those three, which you all know well.

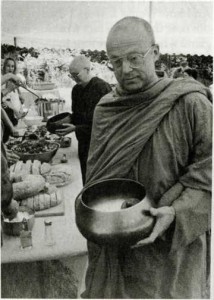

Bhante Gunaratana: Thirty years ago we had maybe 100 Buddhists in this country. Buddhism had not left university campuses. Now it is slowly moving into the mainstream. Therefore, I believe that in twenty years there’ll be more nuns, more monks, more Buddhist temples, more Buddhist practices and more yogis. Buddhism will thrive in this country…. I wish I lived for twenty years to come back and see and meet you all.

Ajahn Passano: When Ajahn Chah first came to the West, he was saying how pleased he was to see the Dhamma flourishing in the West. He felt that it was like planting a tree, and the tree would grow up and the fruit would be coming. In Thailand (where I live) the tree is old. It’s dying, and there’s not so much fruit anymore. Ajahn Chah had a great confidence that this [the West] is where Buddhism would flourish. It’s amazing how much already is happening.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu: I’d hope to see a sense of greater ease between the monastic and lay teachers, a sense that we are all working together. As part of that, I would like to see in the general culture a sense that the monastic alternative for men and women is a viable option, more than it is at the moment. Also, an appreciation that having monasteries is not simply for the monks and nuns, but it’s a place where lay people can come as well for their own practice. Connected to this is seeing that teaching the Dhamma is not just teaching meditation. Being a teacher of the Dhamma means that your entire life has to embody and express the Dhamma.

Steven Smith: I would hope that in twenty years it’s just a short walk from here to a monastic center with nuns and monks, both. I feel as if we’re quite blessed, all of us here, since we’re positioned as a bridge between East and West and between a past era and the present world. We have a role in renewing structures that invite more participation, free of oppression and discrimination and gender insensitivity and so forth. It’s an exciting time. And there’s no one in this room who is not a part of that.

Vimalo Kulbarz: I would also like to see an openness between the different traditions of Buddhism to seeing what we have in common rather than what separates us. Another interesting development could be our finding different forms of communities dedicated to the practice of the Dhamma. I think there is a great potential for lay people in coming together and living in a community where they have the space to be themselves and to allow the Dhamma to come to some fruition. I also would agree with Larry when he feels a little uneasy about the boom in Buddhism. The great danger in all spiritual traditions is too much success and too much recognition. I only hope that we’re not overwhelmed by Buddhism becoming too popular.

Larry Rosenberg: I went to a very, very deep place in my meditation just now, really deep. So this isn’t speculation. This is what’s going to happen, [laughter] Jon Kabbat-Zinn will be the new president of the United States. Joseph will be selected as supreme patriarch and will have this long robe with a crown. And he’ll sit up very high and give one- line dharma talks. There’ll be a monastery down the road. And there’ll be a very smooth connection between the study center and IMS with everyone fluent in Pali, reading the Suttas, and just going from the cushion to the library to the computer with great ease. I think it’s going to be fantastic. And I hope they give me the day off from the nursing home to come down here and see!