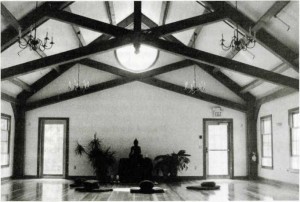

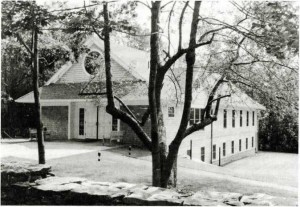

On October 11, 1994, an inauguration ceremony took place at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies to mark the completion and occupation of a significant new building. Built entirely with donated funds, the building is comprised of a large meditation hall/conference room/meeting room upstairs with a foyer that can also be used in a variety of ways, and 14 single rooms on the lower floor equipped for both study and practice. The new facility allows the study center now to host between fifty and a hundred day visitors and more than 14 students overnight.

The following is adapted from a talk given as part of the inauguration ceremony by Andrew Olendzki, executive director of both the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies and the Insight Meditation Society.

All who are gathered here today to help us recognize this important transition are most welcome. I would like to add my thanks and appreciation to those just offered by the study center’s director Mu Soeng—there are so many people present today who have played such crucial roles in the development thus far of the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies.

All who are gathered here today to help us recognize this important transition are most welcome. I would like to add my thanks and appreciation to those just offered by the study center’s director Mu Soeng—there are so many people present today who have played such crucial roles in the development thus far of the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies.

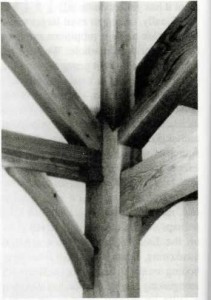

This is indeed a very auspicious moment, for a number of reasons. To begin with, this beautiful building is finally finished; and I think I speak for all of us in saying it has turned out even better than we could have hoped during the early stages of its conception. Not only has it been completed on schedule and on budget (for which we have project manager Bob Trammell to thank), but almost everyone who has been here since its completion had remarked upon the special ambiance of tranquillity and profundity the building seems to create.

But this is an auspicious moment in much larger ways as well. This project would not have been possible were it not for the maturation and stabilization of the Insight Meditation Society next door. For almost twenty years now IMS has, in its own quiet way, proven that there is in our society a wide-ranging interest in the dhamma and in vipassana meditation. The whole enterprise of the study center, manifest so dramatically in this moment by the building surrounding us, grows out of this modern enthusiasm for dhamma and testifies to the success of the basic mission of IMS. For this success we have those brave founding teachers to thank, along with all the other teachers who have come each year to Barre to lead retreats, the considerable number of dedicated souls who have staffed the center over the years, and, perhaps most of all, the thousands of people who have come to Barre—year after year—to persevere in their silent practice of meditation.

But we should recognize that this is not just a local event. I would like to think this is an auspicious moment for the dhamma as well. Viewed from the larger perspective of the last 2500 years, I think our gathering here today for this purpose proves that yet another of the many seeds from the Bodhi tree, spread around the world and across the ages, has taken root in a new world. Preserved for so long and adapted so creatively throughout Asia, the legacy left by the Buddha is in considerable peril in its various homelands, and I am sure the future intellectual and religious history of this world will record the coming of the dhamma to the West as an event significant to its very survival. At the same time, with a tangle of world views already crowding the garden, the dhamma faces the daunting task of adapting to perhaps the most challenging environment it has yet encountered.

Finally, taking an even larger view, I think this to be a propitious moment for the world as a whole. We here all know that the current generations of the world are facing a crisis of unprecedented proportions—environmental, demographic, social and spiritual. We are so much in need of wisdom, compassion and skillful action these days that any source of these influences—from whatever era and whatever cultural origins— will become the most precious of resources for humanity as a whole. I, for one, am quite encouraged that in this, perhaps our darkest hour, there is a glow on the Eastern horizon of a gradual awakening. Despite the prodigious foreboding we are all becoming familiar with recognizing, our generation has also seen a quite promising opening up to the forces of clarity.

***

Which brings me to the subject I have been asked to speak on today: Why did we build this building? What are we going to do with it? What, in short, is the essential mission of the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies?

Last night I was asked a question by my eight-year-old son which has helped me formulate a response to these questions. He asked, “Where are we on the world? Are we on the top, or on one of the sides? And if so, which side are we on?” In trying to explain gravity, and how we can all cling without effort to a spherical ball waltzing through the void, I recognized that there are really only two directions in the universe: inward and outward. In the same way, I think the study center’s mission can be described by both an inward and outward orientation.

Last night I was asked a question by my eight-year-old son which has helped me formulate a response to these questions. He asked, “Where are we on the world? Are we on the top, or on one of the sides? And if so, which side are we on?” In trying to explain gravity, and how we can all cling without effort to a spherical ball waltzing through the void, I recognized that there are really only two directions in the universe: inward and outward. In the same way, I think the study center’s mission can be described by both an inward and outward orientation.

Much of what we hope to do here is face inward, to the core of the Buddhist tradition, to the teaching and its practice, in order to try continually to better understand what has been passed down to us. Despite the clarity of the texts, the skill of their commentators, the wisdom of our teachers, and the occasional lucidity of our own experience during practice, we can never be complacent about having fully understood something as”deep and profound” as the dhamma. Continual investigation of both the theory and the practice of the Buddha’s teaching has been encouraged from earliest times. A few examples:

At one point in the Pali texts the Buddha is attributed as saying of his teaching:

The dhamma has been well proclaimed by the Buddha, is visible here and now, timeless, inviting inspection, leading onward, to be comprehended by the wise each one for him or herself. (D16.2.9)

Elsewhere in the texts, when the Buddha was about to pass away and his followers were concerned about the continuity of his teaching, he is said to have remarked:

It may be that you will think: “The Teacher’s instruction has ceased, now we have no teacher!” It should not be seen like this, for what I have taught and explained to you as the teaching and the practice will, at my passing, be your teacher. (D16.6.1)

Also, several criteria are given for being able to discern whether a statement is in accord with the dhamma or not: Suppose a person were to say to you:…”This is the teaching, this is the practice, this is the Buddha’s doctrine….” Their words and expressions should be carefully studied and compared with the Suttas and reviewed in the light of the practice. (D16.4.8)

And finally, when Ananda is asked after the passing of the teacher how one is now to know the teaching and practice rightly, he says that people with certain qualities can be relied upon for this. One of the ten qualities inspiring confidence is:

A person has learned much, remembers what s/he has learned, and consolidates what s/he has learned. Such teachings as are good in the beginning, good in the middle and good in the end, with the right meaning and phrasing, and which affirm a holy life that is utterly perfect and pure—such teachings as these s/he has learned much of, remembered, mastered verbally, investigated with the mind, an penetrated well by view. (M108.15)

All of these are specific injunctions from the Pali texts to investigate the dhamma and vinaya, the teaching and the practice (in the larger sense of vinaya as the life-style and practical behavior associated with each of the ancient teachings of the Buddha’s day.) This, I submit, is a large part of what we are here to do—to carefully inspect the teaching and the practice. Ours is not a tradition of edicts or ecclesiastical pronouncements; if we can help provide the tools and conditions by means of which everybody who wishes can investigate the dhamma for themselves, then we have offered an important service.

By providing a well-focused library with both primary texts and secondary writings; tools for research, analysis, comparison and linguistic study; tapes of dhamma talks by various modem teachers and newsletters from dhamma centers around the world; by hosting visiting scholars, monks and nuns in residence, conferences, seminars and study groups; by fostering communication between the many Buddhist traditions; by linking electronically with like-minded people from all over the virtual world; by writing and publishing and teaching and learning—by doing all this and more we will all help each other investigate the dhamma for ourselves. By reaching out to include the scholars of the secular academy, and grounding our own curriculum in the practice of meditation and right action, by striving to make all feel welcome here—monk and nun of every vehicle, lay person, scholar, Buddhist or non-Buddhist—we hope to build new bridges and tear down old walls.

By providing a well-focused library with both primary texts and secondary writings; tools for research, analysis, comparison and linguistic study; tapes of dhamma talks by various modem teachers and newsletters from dhamma centers around the world; by hosting visiting scholars, monks and nuns in residence, conferences, seminars and study groups; by fostering communication between the many Buddhist traditions; by linking electronically with like-minded people from all over the virtual world; by writing and publishing and teaching and learning—by doing all this and more we will all help each other investigate the dhamma for ourselves. By reaching out to include the scholars of the secular academy, and grounding our own curriculum in the practice of meditation and right action, by striving to make all feel welcome here—monk and nun of every vehicle, lay person, scholar, Buddhist or non-Buddhist—we hope to build new bridges and tear down old walls.

So this is the great inward direction of the study center’s mission: To carefully study the teachings and review them in light of the practice, with whatever tools the human mind and the modern world provide us.

***

And this is the great outward direction of our mission: To encounter our unfolding world, applying what we learn from the inward view to help ease suffering and nurture compassion, to seek wisdom wherever it may be found, and to guide action to whatever extent possible away from greed, hatred and delusion and toward clarity and understanding.

We need to recognize from the outset, as I think all of us here today already do, that our study of the teaching and the practice increases in value directly in proportion to the degree it is applied in our lives. We are not in the business of designing rafts, but of navigating the waters of the flood. The investigation of dhamma is made worthwhile only by the application of dhamma, on an individual, community and global level.

There are so many ways these teachings and their practice can be of value to the modern world, and the exploration of these applications is already an exciting part of the mission of the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. Beginning with the alleviation of suffering—physical, mental, emotional and spiritual—our mission includes furthering the application of dhamma to the healing, caring and counseling professions. Many of you here are pioneers in this field, and know firsthand how effectively the simple balms of kindness, tranquillity and insight can ease many kinds of pain.

Our mission also includes the nurturing of compassion, a teaching for which the world is now particularly in need. The Buddha’s injunction to do no harm to any living creature, whether human or nonhuman, a member of our own culture or one alien to us, to others or even to ourselves, needs to be continually rearticulated and reintroduced to every modem arena of conflict. We have hardly begun exploring this important work.

The teachings of wisdom, of seeing things as they really are rather than as projections of our own assumptions and desires; of understanding causality, how one thing leads inevitably to another, for better or for worse; of perceiving the profound interdependence of all things, all beings and all systems; and of recognizing the essential insubstantiality of that smidgen of reality we call ego or self—all these are so very valuable and potentially transformative that we have a duty to translate these timeless truths in ways that can influence our world.

And lastly, our mission includes the subtle but clear guidance of personal, communal and universal action away from what is harmful or unhealthy and towards what is helpful and wholesome. The dhamma teaches a path of freedom, the freedom to chose our individual and collective destinies by skillful perception of what is beneficial and what is detrimental, and all of us here have a role in helping to shine light on this path. All action is preceded by intention, and intention can be influenced either by ignorance or by wisdom. We have the power to chose—day by day and moment by moment—what is skillful over what is unskillful, if only we can develop the clarity to discern the difference.

Just as the human race did not acquiesce to what it was bom with—short teeth, dull nails and a naked body—but used its cleverness to forge a civilization to overcome these physical limitations, so also the Buddha has taught us that we need not acquiesce to the greed, hatred and delusion endemic to the human condition. Like a potter, we can mold our consciousness with our intentions; like an irrigator, we can guide action, speech and thought away from doing harm and toward acts of kindness; like a fletcher, we can straighten our character; and like a farmer, we can plow and sow in the field of action to reap the fruits of wisdom.

So please, all of you gathered here today, on this most auspicious occasion … please join me in dedicating this beautiful new building and all it stands for, to the investigation of dhamma through study, practice and the creative exchange between the two; to the application of dhamma in the present and future for the alleviation of suffering, the nurturing of compassion, the seeking of wisdom and the skilful guidance of action. For indeed the promise of our work here goes far beyond these timber-framed walls. We have the potential to contribute significantly to the transformation—and possibly thereby also to the salvation—of ourselves and our civilization.