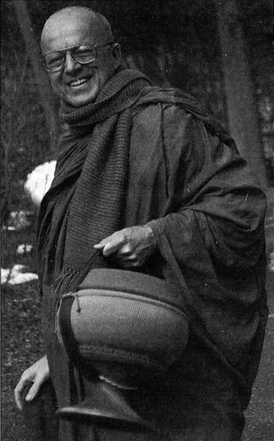

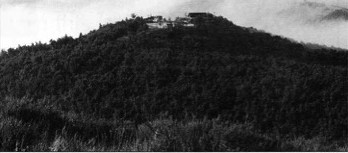

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, also known more informally to many as Ajaan Geoff, is an American-born Theravada monk who has been the abbot of Metta Forest Monaster near San Diego, CA, since 1993. He teaches regularly at BCBS and throughout the US and has contributed significantly to the Dhamma Dana Publications project with his books Wings to Awakening, Mind Like Fire Unbound, and a new free-verse translation of the Dhammapada.

Ajaan Geoff, thirty years ago you were a student at Oberlin College. Now you’re the abbot of a Buddhist monastery near San Diego. Could you tell us a little about how you got from there to here?

The route was a lot less roundabout than you might think. Like many college students, I was obsessed with deciding what to do with my life. Business, government, academia: I couldn’t see myself finding happiness in any of them. I didn’t want to lie on my deathbed, looking back at a life frittered away. Fortunately, in my sophomore year, I was introduced to Buddhist meditation, and I took to it like a duck to water.

After graduation I decided to take a break in my education to go teach in Thailand—to get some perspective on my life, and maybe find a good meditation teacher. While I was there I met Ajaan Fuang, perhaps the first truly happy person I had ever met. He embodied the dharma [the teachings of the Buddha] in a way that I found appealing: wise, down-to- earth, no-nonsense, and with a sly sense of humor. Whatever happiness and wisdom he had, he told me, was due entirely to the training. That was when I realized I had found something to which I could devote my entire life. So I ordained to train with him, and I’ve never regretted my choice.

Ajaan Fuang trained you as a meditation monk, but for the past several years you’ve also been translating and explaining the Pāli sutta(s) [the early Buddhist texts]. How do you find that studying the suttas helps with meditation?

The Buddha in the suttas asks all the right questions. We all know that what we see is shaped by the views we bring to things, but we’re often not aware of the extent to which our views are shaped by the questions we ask ourselves. The Buddha had the good sense to see that some questions are skillful—they really do point you to freedom, to the total cessation of suffering—while others are unskillful: they take you to a dead end, tie you up in knots, and leave you there. The suttas are helpful in showing how to avoid getting involved in unskillful questioning. If you listen carefully to their advice and take it to heart, you find that it really opens your eyes to how you approach meditation and life in general.

There are currents in modern dharma teaching that de-emphasize the importance of the historical discourses. One might say, for example, “Don’t we often hear that the Buddha said not to believe texts and traditions?”

Well, he didn’t say to reject them out of hand, either. Have you ever noticed how American dharma is like the game of Telephone? Things get passed on from person to person, from one generation of teachers to the next, until the message gets garbled beyond recognition.

I once received a postcard on which the sender had rubber-stamped the message, ‘”Don’t believe anything outside your own sense of right and wrong.’—The Buddha.” That was apparently meant to be a quote from the Kālama Sutta, but when you actually read the sutta, you find that it says something much more sophisticated than that: You don’t believe something just because it’s handed down in the texts or taught by your teachers, but you don’t accept it just because it seems logical or fits in with your preferences, either. You have to put it to the test, check it in terms of actual cause and effect. If you then find that it leads to harm and is criticized by wise people, you stop doing it. If it’s beneficial and praised by wise people, you stick with it. Notice, though, that you don’t go solely by your own perception of things. You look for wise people and check your perceptions against theirs. That way you make sure you’re not simply siding with your own preconceived notions.

And so the suttas can serve as kalyāṇa mitta(s), or “wise friends?”

There is no real substitute for spending time in close contact with a really wise person, but the suttas can often be the next best thing—especially in a country like ours where wise people, in the Buddhist sense of the term, are so few and far between.

You mentioned that the suttas label certain questions as unskillful. Some of these may be fairly obscure philosophical issues that no longer interest anyone, but can you point to any that are relevant to meditators at present?

The big one is, “Who am I?” There are dharma books telling us that the purpose of meditation is to answer this question, and a lot of people come to meditation assuming that that’s what it’s all about. But the suttas list it as a fruitless line of inquiry.

Why is that?

Good question (laughs). As far as I can see, the response is this: What sort of experience would give you an answer to that question? Can you imagine any answer to that question that would put an end to suffering? It’s easier to be skillful in any given situation when you don’t saddle yourself with set ideas about who you are.

Might the anattā doctrine be considered the Buddha’s answer to the question, “Who am I?”?

No. It’s his answer to the question, “What is skillful?” Is self-identification skillful? Up to a point, yes. In the areas where you need a healthy, coherent sense of self in order to act responsibly, it’s skillful to maintain that sense of coherence. But eventually, as responsible behavior becomes second nature and you develop more sensitivity, you see that self-identification, even of the most refined sort, is a form of clinging. It’s a burden. So the only skillful thing is to let it go.

How would you respond to those who say they get a sense of oneness with the universe when they meditate, that they’re interconnected to all things, and that it relieves a lot of suffering?

How stable is that feeling of oneness? When you feel like you’ve come to the stable ground of being from which all things emanate, the suttas ask you to question whether you’re simply reading that feeling into your experience. If the ground of being were really stable, how would it give rise to the unstable world we live in? So whatever it is you’re experiencing—it may be one of the formless states—it’s not the ultimate answer to suffering.

On an affective level, a sense of connectedness may relieve the pain of isolation, but when you look deeper, you have to agree with the Buddha that interconnectedness and interdependence lie at the essence of suffering. Take the weather, for instance. Last summer we had wonderful, balmy weather in San Diego—none of the oppressive heat that usually hits in August—and yet the same weather pattern brought virtually non-stop rain to southern Alaska, drought to the Northeast, and killer hurricanes with coffins floating out of their graves in North Carolina. Are we supposed to find happiness in identifying with a world like this? The suttas are often characterized as pessimistic in advocating release from saṃsāra, but that’s nothing compared to the pessimism inherent in the idea that staying interconnected is our only hope for happiness.

Yet so many people say the desire for release is selfish.

Which makes me wonder if they understand how we can be most helpful to one another. If the path to release involved being harmful and cold-hearted, you could say it was selfish; but here it involves developing generosity, kindness, morality, all the honorable qualities of the mind. What’s selfish about that? Everyone around you benefits when you can abandon your greed, anger, and delusion. Look at the impact that Ajaan Mun’s quest for release has had for the last several decades in Thailand, and now it’s spreading throughout the world. We’d be much better off if we encouraged one another to find true release so that those who find it first can show the way to anyone else who’s interested.

And the way to that release starts with the question, “What is skillful?”

Right. It’s the first question the Buddha recommends that you ask when you visit a teacher. And you can trace this question throughout the suttas, from the most basic levels on up. There is a wonderful passage where the Buddha is teaching Rahula, his seven-year-old son [Ambalatthika Rahulovada Sutta, M 61]. He starts out by stressing the importance of being truthful—implying that if you want to find the truth, you first have to be truthful yourself— and then he talks about using your actions as a mirror. Before you do anything, ask yourself: “Is what I intend to do here skillful or unskillful? Will it lead to well-being or harm?” If it looks harmful, you don’t do it. If it looks okay, you go ahead and give it a try. While you’re doing it, though, you ask yourself the same questions. If it turns out that it’s causing harm, you stop. If not, you continue with it. Then after you’ve done it, you ask the same questions—”Did it bring about well-being or harm?”—and if you see that what originally looked okay actually ended up being harmful, you talk it over with someone else on the path and resolve never to make that mistake again. If it wasn’t harmful, you can take joy in knowing that you’re on the right track.

So the Buddha is giving basic lessons in how to learn from your mistakes.

Yes, but if you look carefully, you’ll see that these questions contain the seeds for some of his most important teachings: the role of intention in our actions; the way causality works—with actions giving immediate results along with long-term results; and even the four noble truths: the idea that suffering is caused by past and present actions, and that if we’re observant we can find how to act more and more skillfully to a point of total freedom.

And how would you apply this to meditation?

It starts with your life. We all know that meditation involves disentangling yourself from the narratives of your life so that you can look directly at what you’re doing in the present. Now, some narratives are easier to disentangle than others. If you’re acting in unskillful ways in daily life—lying, having illicit sex, taking intoxicants—you’ll find that you’re creating some pretty sticky narratives, all coated with denial and regret. So you apply the Buddha’s line of questioning to your day-to-day life in order to clean up your act and provide yourself with new narratives that are easier to let go.

At the same time, in doing this, you’re developing the precise skills you’ll need on the meditation cushion. Getting into the present moment is a skill, and it requires the same questioning attitude: observing what the mind is doing, seeing what works, what doesn’t work, and making adjustments where needed. Once you get into the present moment, you use the same line of questioning to investigate the present, taking it apart in terms of cause and effect: present action, past action, present results. Once you’ve taken apart every mental state that clouds the brightness of your awareness, you then turn the same questions on that bright awareness itself, until there’s nothing left to question or take apart any further—not even the act of questioning itself. That’s where liberation opens up. So these simple questions can take you all the way to the end of the practice.

Was this how you were taught meditation in Thailand?

Yes. The one piece of advice Ajaan Fuang stressed more than any other was, “Be observant.” In other words, he didn’t want me simply to follow a method blindly without monitoring how it was working out. He handed me Ajaan Lee’s seven steps on breath meditation and told me to play with them—not in a desultory way, but the way Michael Jordan plays basketball: experimenting, using your ingenuity, so that it becomes a skill. How else can you expect to gain insight into the patterns of cause and effect within the mind unless you play with them?

Are there any other questions from the suttas that strike you as particularly relevant to the American dharma scene?

Two jump immediately to mind. One has to do with evaluating teachers. The suttas recommend that a student look carefully at a person’s whole life before accepting him or her as a teacher: Does this person embody the precepts? Can you detect any overt passion, aversion, or delusion in what this person says or does? Only if someone can pass these tests should you accept him or her as a teacher.

This calls into question an attitude that’s becoming increasingly prevalent here in the US. A teacher once said, not too long ago, “As long as a teacher points at the truth with one hand, it doesn’t matter what he or she does with the other hand.” Now, is the dharma something you can point to with only one hand? Can the other hand ever really be invisible? There’s a real drive at the moment to turn out teachers to fill the demand for retreat leaders, but if they feel they can afford a one-handed attitude, we’ll end up with teachers who are little more than mindfulness technicians or yogi-herders: people whose job is to get students safely through the retreat experience, but whose personal life may be teaching an entirely separate lesson. Is that what we want?

If it is, we are setting people up for trouble. So far the mindfulness community has avoided many of the scandals that have ravaged other American Buddhist communities, largely because it hasn’t been a community. It’s more a far-flung network of retreat clientele. The teachers’ personal lives haven’t had that much direct bearing on the lives of the students. But now local communities are beginning to develop, where students and teachers have close, long-term contact with one another. Can we imagine that what each teacher does with that other hand is not going to have an impact on the students’ lives and their respect for the dharma? If we don’t start now to rely more on the suttas’ method for evaluating teachers, we’ll have to start reinventing the dharma wheel after people get hurt, which would be a great shame.

And the other question?

Renunciation. What do we have to give up if we want true happiness? Do we have unlimited time and energy to pursue an unlimited number of goals? Or do we need to sacrifice some of the good things in life in order to gain the most valuable form of happiness? This is a huge blind spot in American Buddhism.

Once, just out of curiosity, I went through a pile of Western dharma books and magazines, looking up the topic of renunciation. Most of them didn’t even mention it. From the few that did, I learned that renunciation means, one, giving up unhealthy relationships; two, abandoning your controlling mind-set; and three, dropping your fear of the unknown. Now, we don’t need the Buddha to tell us those things. We can learn the first lesson from our parents, and the other two from a good therapist. But the Buddha recommended giving up a lot of things that most well-meaning parents and therapists would tell their children and patients to hold onto tightly. And yet you don’t see any mention of this in American dharma.

Is that because Americans tend to live more comfortable lifestyles?

Not necessarily. Modern mass culture, whether Asian or American, is a lot more indulgent than traditional culture, but that may be because it’s a lot more frenetic and stressed out as well. The Buddha himself said that, when he was starting out on the path of practice, his heart didn’t leap up at the idea of renunciation. Nobody wants to hear that true happiness involves giving up the things we like, but at least in Asia there are dharma masters who, through their words and actions, keep pumping that lesson into the culture. So it’s always there for honest, mature, reflective people to hear. But here in the West, the dharma has been so shaped by the marketplace that the lesson is very seldom modeled.

Last year Tricycle printed an article bemoaning how the dharma is being used to sell mass-market commodities, but a deeper problem is that the dharma has become a commodity itself. I was in a bookstore recently with a student, and as we looked at the many shelves filled with books on Buddhism, he asked me, “Do you get the impression that these books were written to make money?” How can you expect to learn the hard lessons of renunciation from a book that had to get past marketing directors and sales reps? And given the financial needs of most teachers, how can you expect even well-meaning teachers not to shape their message to conform with what people want to hear, as opposed to what they should hear?

You’ve written on what you call the “economy of gifts,” in which the dharma can be offered freely with no strings attached. How do you think such an economy could be implemented here in America?

It’s a long, uphill process, but yes, it can happen. You have to start small—a few good monasteries here and there, a few dāna-based organizations such as the Dhamma Dāna Publication Fund and now the Dharma Seed Tape Library—and eventually people will catch on to what a good thing it is. Of course, the fact that dharma is free doesn’t necessarily guarantee that it’s going to be top-quality, but at least it hasn’t been filtered through the sort of bottom-line concerns that we needlessly take for granted. It’s only when we appreciate the need to have the bottom line totally out of the picture that American dharma will have a chance to mature. Which makes me wonder if dāna-based dharma will always be something of a fringe phenomenon in our country.

From our discussion so far, you seem to see the Pāli suttas as offering not only right questions, but also right answers.

The right answers are the skillful choices you make in your life as you pursue the right questions. I think it was Thomas Pynchon who said, “As long as they can get you to ask the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about the answers.” There should be a corollary to that: As long as you honestly stick to the right questions, you’re sure to arrive at answers that will make a difference.

Of course, many people in our society are uncomfortable with the notion of right and wrong–especially in the area of religion.

I don’t think it’s so much that they are uncomfortable with the notion of right and wrong. It’s just that they’ve shifted their reference points. Being judgmental is now wrong; being non-judgmental is right. This, I think, comes from two factors. One is that we’re tired of fervid monotheists who demonize anyone who differs from their view of The One True Way. We’ve seen the harm that comes from sectarian religious strife, and it’s obviously pointless. So we want to avoid it at all costs. The other factor is that we ourselves have been subject to evaluation all of our lives, some of it pretty unfair—in school, at work, in our relationships—so when we come to retreats we want respite.

This becomes a problem, though, when people confuse being judgmental with the act of exercising judgment. And again, the difference is a question of skill. Being judgmental—hypercritical, quick to dismiss the opinions of others—is obviously unskillful. But in our rush not to be judgmental, we can’t abandon our critical abilities, our powers of judgment. We have to learn how to use them skillfully. It’s all very fine not to pass judgment when you’re on the sidelines of an issue and don’t want to get involved. But here we’re all out on the playing field, facing aging, illness, and death. Our skill in exercising judgment is going to make all the difference in whether we win or lose. The team we’re facing has never been taught to be uncritical. They play hard, and they play for keeps.

The Buddha himself was quite critical of teachers who wasted their time—and that of their students—by asking the wrong questions. He was especially critical of those who misunderstood the nature of karma, because how we comprehend the power of our actions is what will make all the difference in how skillfully we choose to think and act. So refraining from judgment is not the answer to the question of how we face the differing teachings we find available. In fact, a knee-jerk non-judgmental stance can often be a very unskillful way of passing judgment.

How so?

How so?

It’s a refusal to take differences seriously, and that totally short-circuits any attempt to develop skill. You often find this associated with a lowest-common-denominator approach to the truth: the assumption that whatever the major traditions of the world hold in common must be true, while their differences are only cultural trappings. But that’s assuming they’re all asking the same questions, or that the only important questions are the ones they all ask. Where does that leave people who think outside the box?

I’ve seen some elaborate attempts to create a perennial philosophy from the common ground of the world’s great traditions, but they center on the question, “Who am I?” That, they tell us, is the question at the heart of everyone’s spiritual quest. But the training I got from Ajaan Fuang taught me to question the assumption that that’s a fruitful line of inquiry. Does the fact that everybody else is asking it mean he was wrong?

Another approach is to assume that all traditions take you to the same place, but that they’ve found different skillful ways of doing it—the old “many paths lead to the top of the mountain” idea. But the reports we get from people who have been up this mountain say that it has plenty of wrong turns, false summits, and sudden drop-offs. One tradition will say, “When you reach this point, turn left.” Another will say, “If you turn left at that point you’ll get stuck at a dead-end.” If we plan to stay on the valley floor, it’s okay for us to stay out of the argument. But can we claim some sort of higher moral ground for not getting involved in the fray? Do we have more comprehensive maps of the mountain showing that dangers are imaginary, and that left turns and right turns are all okay?

There are dharma books telling us that the purpose of meditation is to answer the question, “Who am I?” But the suttas list this as a fruitless line of inquiry.

Or suppose that one tradition says, “The summit looks like this.” Another says, “No, that’s a false summit. The real one looks like this.” The first one responds, “No, you’re at the false summit.” Do we know the limitations of language better than they do, so that we can dismiss their differences as purely linguistic? If we want to go up the mountain, we have to choose one guide or the other—or maybe a third guide, if we decide that the first two were both on the wrong path.

So how would you choose?

One, take a good look at the teachers. If people are skilled mountaineers, they should have no trouble negotiating the valley. Can they get around without injuring themselves or others? Has their experience of the summit been so overwhelming that they’re willing to sacrifice personal comfort so that others can get there as well?

Two, look at the tradition. What kinds of questions does it focus on? What kinds does it allow? What kinds does it not allow? Why? Does it encourage the tenacity and maturity needed to stick to a hard line of questioning? Does it foster the kind of ingenious, observant mind that would recognize a false path or figure out a way past an unexpected obstacle?

Finally, take a good look at yourself. Are you up for the adventure? It may sound more than a little intimidating, but the Buddha asked of his students simply that they be honest enough to admit and learn from their mistakes, and sensible enough to give up a lesser happiness when they see that, by doing so, they’ll gain a higher one. Are you up to that? If so, you’ve got what it takes.